In the June 26, 2018 Ask The Headhunter Newsletter a reader says the quickest job offers come from quick and easy interviews. So we consider why.

Question

Difficult job interviews tend to be grueling and I never get offers. I have discovered that interviews which end up in a job offer are short and I come away wondering why they didn’t ask me hard questions.

That’s how I got my current job. The managers made their decision right there and then. I expect to get an offer from another recent interview that went just as well. (I will probably turn it down.) They didn’t actually say so, but the message was clear: They’re definitely interested and they seem hopeful I’ll accept a job.

Another example: I got my previous job when my manager made the decision during the phone interview while I was 2,000 miles away. My on-site interview was about an hour and ended up with an offer on the spot.

In contrast, after recent discussions with an iconic company known for its difficult interviews, I realized that I would have to neglect my current job (which I love) to make preparations to interview successfully. Even though the company has exciting technology that excites me, I shut down the process. [See How and when to reject a job interview.]

The latest company that wants me has technology as interesting as the iconic company. They are not well known, but they are very certain about why they want to hire me. It pays to look for gems like these.

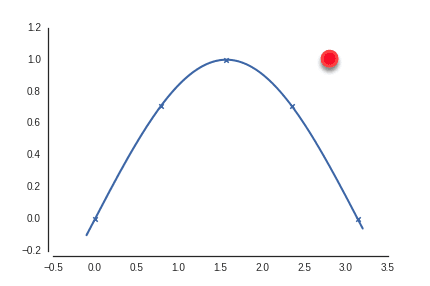

So I am concluding that if someone has decided they are interested in you, the interview will be pretty easy and the offer will come quickly. If they are not interested, they might throw some difficult questions your way to “reveal” your incompetence. (At the iconic company, they kept asking question after question until I couldn’t answer.) Then they say to one another, “Obviously, this is not a good candidate — he couldn’t answer a basic question!”

I don’t want to work for people like that. What do you think of my observations?

Nick’s Reply

You’ve pointed out a very interesting phenomenon in hiring that seems to sail over most people’s heads. Some hiring decisions happen quickly, and the interviews are smooth. What makes an interview go so well?

But I think everyone gets so wrapped up in the interview game that they totally ignore an even more important question:

Why?

Why do interviews happen?

That is, Why is the interview happening at all?

We can break this down into two more specific questions:

- Why did the employer choose this candidate?

- Why did the candidate choose the company?

I think there are several answers, and they reveal the stark difference between employers who know what they are doing and those that are clueless about recruiting and hiring. It’s all about what happens way before the interview even gets scheduled.

When job seekers and employers choose one another for the right reasons, interviews seem easier and job offers materialize quickly. But I don’t have to tell you this doesn’t happen effortlessly!

5 Steps to Quick Job Offers

I find that employers that hire quickly and decisively take most of these five steps before they conduct interviews. In fact, they take these steps before they even contact any candidates.

- The employer decides where to find the right candidates.

These trusted sources might be other people, organizations, specialized pools or communities, or even publications. The candidate list is not generated by algorithms, job boards or databases. Thus, only high-likelihood candidates are ever interviewed.From Fearless Job Hunting – Book 3: Get in The Door (way ahead of your competition), p. 8:To get your feet in the manager’s door, don’t throw resumes at it. It’s the people, Stupid. That manager has no time to read your resume because he’s busy talking to a candidate referred by people he trusts. To get in the door, you need those people to introduce you. And the manager needs someone who has a plan to get the job done. Make that person you.

- The employer decides what outcomes it wants from the hire.

So, it pre-selects people who are able to deliver outcomes, not qualifications or keywords on resumes. These candidates are not surprised by the criteria and interview questions, and the meetings go smoothly. - The employer understands that specific skills are not the objective in selecting candidates.

The main objective is to hire someone with the ability to ride a fast learning curve without falling off. That is, the right candidate is someone who can learn whatever is necessary to get the work done. You don’t find that on a resume or in a job application. Of course, there are prerequisites, but most of the time these can be verified prior to even contacting the candidate. - The employer vets candidates before it contacts them.

It does its background research in advance, by turning to trusted sources of good information. I’m not talking about background checks. I’m talking about referrals, recommendations and firsthand knowledge about the person. Thus, only high-likelihood candidates who can readily address the employer’s needs are ever recruited or interviewed. - The match is made mostly in advance.

The employer is already more than halfway there on the hire, before the interview happens, because it already knows a lot about the candidate. The interview is not the main assessment; it’s a confirmation. The chance of a quick hire skyrockets.

Good candidates don’t come in a grab-bag

It’s no accident or coincidence that this approach to hiring mirrors how good managers do other aspects of their jobs. A good interview is good business.

For example, an engineering manager doesn’t design and build a new widget by dumping a grab-bag of random parts on her team’s desk. She and her team carefully research available parts and their manufacturers, confirm quality in advance, and lay out on their workbench only the parts they already have a lot of faith in. The same goes for picking people.

Why are employers so game to buy a grab-bag of applicants from LinkedIn or Indeed?

Most candidates should be “wired” for a job

This is not to say that a sharp manager with good insight can’t identify a great candidate on the spot, when that candidate is essentially “off the street” with no background research done at all. In such cases, I think the manager has an unusual — but absolutely critical — grasp of exactly the kind of person they want. The manager recognizes that person when they appear, has the authority to move quickly, and acts decisively to make a quick offer.

But I believe that most of the time when such quick hires happen, it’s because the real legwork has been done in advance. You’ve no doubt heard the old saw about a lawyer questioning a witness in court: Never ask the witness a question you don’t already know the answer to. The same holds for job interviews — except most employers won’t be bothered to do their homework about the candidate.

When we say someone was “wired” for a job, what we really mean is the employer chose carefully whom to interview in advance. The manager selected from a pool of thoroughly vetted people.

That’s why the right candidate winds up in the interview — and it’s why the interview appears easy and the decision quick.

Avoid broken interviews

I think those offers came quickly to you simply because you were the right candidate and the typical rigmarole of interviewing wasn’t necessary. The rigmarole is necessary only when the employer has no idea what it wants, whom it’s talking with, or how to assess the candidate. The rigmarole signals the interview is broken from the start and that you’ll likely be wasting your time — and so’s the employer.

A broken interview is marked by a canned, indirect assessment process that, almost by definition, isn’t going to yield any helpful insights about the candidate. It consists of the Top 10 Stupid Interview Questions, and it’s about everything except how you would do the work.

As you already recognize, that kind of rote assessment feels very painful and awkward. It’s not a meeting of professional minds or a discussion about the work. It’s an interrogation. The process stretches out mercilessly because the employer never did the legwork. When employers rely on such canned, indirect assessment methods, they feel they can justify hauling in dozens of candidates they know virtually nothing about. “The assessment tool will reveal the best candidates for us!”

No, it won’t. It’s a waste of time. The interview is broken.

Good managers help candidates get hired

This is why fewer candidates are better than lots. Any employer that’s working through a big stack of resumes and applicants likely isn’t sure what it really wants, and is searching in the wrong places and sizing up mostly wrong candidates.

Those interview questions that seem to get you hired quickly seem easy because the employer picked a candidate that can answer them. Why interview anyone else?

This is why I teach hiring managers to talk with a candidate’s professional cohort in advance (while respecting privacy, of course). Then I suggest managers contact their carefully selected candidates and coach them prior to interviews — just like they coach their employees on how to do a project at work. The manager has to want the person to succeed! Only worthy candidates will take the coaching. (See also, Handouts: What information should employers give to job candidates prior to interviews?)

What this means is, employers should not interview anyone that they’re not already excited about hiring.

The match is made in advance

The insights you’ve shared may seem trivial. (“I get hired when the interviews are quick and easy!”) But your insights are profound. Let’s go back to our two questions:

- Why did the employer choose this candidate?

- Why did the candidate choose the company?

If the answer isn’t, “We already know this person and job are a great match!”, then the interview will likely go south because someone didn’t do the necessary legwork. The job interview should be a chance to confirm a match, but a good match should be made in advance. When employers and candidates do the hard work of matching in advance, interviews seem easy and job offers are made quickly.

Do your interview and job-offer experiences mirror this reader’s? What’s the early mark of an interview that will yield a hire? What tips you off that an interview will go nowhere? Whether you’re a job seeker or a hiring manager, what steps can (or do) you take to help ensure an interview will produce a hire?

: :

I know you don’t like Glassdoor’s salary survey data and employer reviews, but what are we supposed to use to base our salary negotiations on? I’m talking about job seekers.

I know you don’t like Glassdoor’s salary survey data and employer reviews, but what are we supposed to use to base our salary negotiations on? I’m talking about job seekers.

An example of natural networking

An example of natural networking When I encounter a job I’m interested in, I don’t apply, I don’t send out my resume on spec, and I don’t write cover letters highlighting relevant experience or how well I might do the job. I don’t sell myself at all.

When I encounter a job I’m interested in, I don’t apply, I don’t send out my resume on spec, and I don’t write cover letters highlighting relevant experience or how well I might do the job. I don’t sell myself at all.

Hank’s evil sister

Hank’s evil sister Thanks for asking. My purpose behind this week’s column is revealed in the title. When we get to the end of it, I’m going to ask everyone to complete that sentence: “We need to know your salary because — .”

Thanks for asking. My purpose behind this week’s column is revealed in the title. When we get to the end of it, I’m going to ask everyone to complete that sentence: “We need to know your salary because — .”

In a recent column,

In a recent column,