In the April 2, 2013 Ask The Headhunter Newsletter, a job hunter complains about HR:

Throughout my career I have gotten new jobs by meeting and talking to managers who would be my bosses. Now I keep running into the Human Resources roadblock in companies where I’d like to talk to a manager about a job. Honestly, I just don’t see the reason for silly online application forms or for “screeners” who don’t understand the work I do, when companies complain they cannot find the right talent. I really don’t get it. Why do companies even have HR departments involved in hiring?

Nick’s Reply

Good question. Better question: Should Human Resources (HR) be in the recruiting and hiring business? My answer is an emphatic NO for three main reasons, though there are many others.

First, HR is qualified to recruit and hire only other HR workers. HR is not expert in marketing, engineering, manufacturing, accounting, or any other function. HR is thus not the best manager of recruiting, candidate selection, interviewing, or hiring for any of those corporate departments.

First, HR is qualified to recruit and hire only other HR workers. HR is not expert in marketing, engineering, manufacturing, accounting, or any other function. HR is thus not the best manager of recruiting, candidate selection, interviewing, or hiring for any of those corporate departments.

Second, HR takes recruiting and hiring out of the hands of managers who should be handling these critical tasks. Finding and hiring good people are two of the most crucial jobs managers have. I offer employers three simple suggestions for improving recruiting:

- Don’t send a Human Resources clerk to do a manager’s job,

- Put your managers in the game from the start, and

- Deliver value to the candidate throughout the job application process.

I think companies suffer when they subject applicants to the impersonal and bureaucratic experience of dealing with HR.

Which brings me to the third reason HR should be taken out of the recruiting and hiring business: HR has no skin in the game. It virtually doesn’t matter who is recruited, processed, or hired because HR isn’t held accountable. It’s hardly HR’s fault, but it’s a rare company that rewards or blames HR for the quality of hiring. HR is typically insulated as a “necessary overhead function.”

Don’t get me wrong: There are some very good people working in HR, and there may be a legitimate role for HR in many companies. But HR’s domination of recruiting and hiring has led to a disaster of staggering magnitude in our economy. In the middle of one of the biggest talent gluts in American history, employers complain they can’t fill jobs.

Don’t miss Harvard Webinar Audio: Can I stand out in the talent glut?

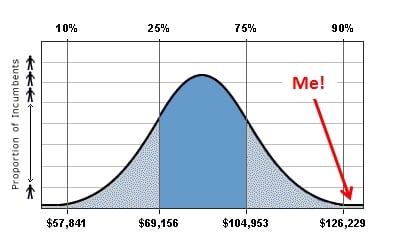

According to PBS NewsHour estimates, there are over 27 million Americans looking for work, either because they are unemployed or under-employed. (The U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports there are 12 million unemployed.) I prefer the NewsHour figure because it tells us just how big the pool of available talent is. Concurrently, BLS also reports there are 3.7 million jobs vacant.

According to PBS NewsHour estimates, there are over 27 million Americans looking for work, either because they are unemployed or under-employed. (The U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports there are 12 million unemployed.) I prefer the NewsHour figure because it tells us just how big the pool of available talent is. Concurrently, BLS also reports there are 3.7 million jobs vacant.

HR has a special term for this 7:1 ratio of available talent to vacant jobs. HR departments and employers call this 7:1 job-market advantage “The Great Talent Shortage!”

While the economy has put massive numbers of talented workers on the street, HR nonetheless complains it can’t find the workers it needs. That’s no surprise when HR’s idea of finding talent is to resort to database searches and keyword filtering, which are disastrously inadequate methods for finding and attracting the best hires.

The typical HR process of recruiting and hiring is most generously described as hiring who comes along via job boards and advertisements. It’s a rare (and precious) HR worker who gets up from behind the computer display to actually go find, meet, and bring home good candidates.

“The typical explanation for why HR recruiters have no time to recruit actively is that they have too many resumes to sort. This very real problem is solved easily: Stop soliciting and accepting resumes.”

Go recruit!

I could write pages about corporate maladies that arise from employers’ over-reliance on HR to recruit and hire. Instead, I’m just going to list some of the ways HR can kill any company’s competitive edge by interfering with these management functions:

Wasting money

Last year, almost a billion dollars was sucked up by just one online “job board,” Monster.com, which was reported as the “source of hires” only 1.3% of the time by employers surveyed. HR could be advocating for the personal touch in recruiting, but blows massive recruiting budgets on job boards with little to show in return.

Hiring who comes along

Job boards and similar advertisements — the high-volume, passive recruiting tools HR relies on — yield only applicants who come along, not those a company should be pursuing.

Wasting good hires

Good candidates are lost because database algorithms and keyword filters miss indicators of quality that are not captured by software. And highly qualified technical applicants are rejected because they are screened not by other technical experts, but by HR, which is too far removed from business units that need to select the best candidates.

Mistaking quantity for quality

HR has turned recruiting into a volume operation — the more applicants, the better. This results in impersonal, superficial reviews of candidates and quick, high-volume yes/no decisions that are prone to error.

Excusing unprofessional behavior

Soliciting far more applicants than HR can process properly results in unprofessional HR behavior, angry applicants and damage to corporate reputations. HR routinely suggests that the high volume of applicants it must process explains its rude no-time-for-thank-yous-or-follow-ups behavior — while it expects job applicants to adhere to strict rules of professional conduct.

Failing to be accountable

Because HR does not report to the departments it recruits for, it tends to behave inefficiently and unaccountably with impunity. The bureaucracy grows without checks and balances, and the hiring process becomes dull, rather than honed to a true competitive edge.

Marginalizing professional networks

HR tends to isolate managers from the initial recruiting and screening process, further deteriorating the already weak links between managers and the professional communities they need to recruit from.

Bureaucratizing a strategic function

The complexity of corporate HR infrastructure encourages isolation and siloing. Evidence of this is HR’s over-emphasis of legal risks in recruiting and its administrative domination of this top-level business function.

Wasting time

With recruiting and hiring relegated to an often cumbersome HR process, managers cannot hire in a timely way. Good candidates are frequently lost to the competition. (HR doesn’t have to deal with the consequences, but when a good sales candidate is lost to a competitor, the sales department loses twice.)

Killing a company’s competitive edge

HR owns two competing interests, further dulling a company’s competitive edge: the hiring process and legal/compliance functions. Because hiring is a strategic, competitive function, it deserves its own advocate. If business units and managers took full responsibility for recruiting and hiring (while HR handled compliance) the daily abrasion of these competing interests would strengthen a company’s edge.

This catastrophe didn’t occur overnight. It crept up on business in the form of a smothering shroud of red tape. Today this HR bureaucracy is propped up by an industry of “consultants,” “professionals,” and “experts” who advise corporate HR departments about how to maintain their administrative stranglehold over the key differentiator that defines any company — its people. And in turn, HR funds the database-induced job-board stupor and online-application-form addiction that’s killing employers and job hunters alike.

This catastrophe didn’t occur overnight. It crept up on business in the form of a smothering shroud of red tape. Today this HR bureaucracy is propped up by an industry of “consultants,” “professionals,” and “experts” who advise corporate HR departments about how to maintain their administrative stranglehold over the key differentiator that defines any company — its people. And in turn, HR funds the database-induced job-board stupor and online-application-form addiction that’s killing employers and job hunters alike.

It’s time for HR to get out of the recruiting and hiring business, and to give this strategic function back to business units and managers who design, build, manufacture, market and sell a company’s products. Who better to decide who’s worth hiring? Who better to aggressively go find the people who will give the company an edge?

In the meantime, job hunters have no choice but to outsmart the employment system.

Should HR relinquish its recruiting and hiring functions? Have you experienced related problems with HR, either as a hiring manager or as a job applicant? What do you think should be done about it? (And if you think I’m wrong, please tell me why.)

: :

That’s where pleasant surprises come from.

That’s where pleasant surprises come from.