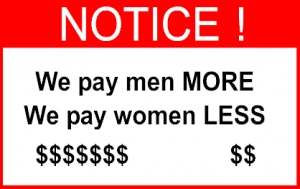

In the April 12, 2016 Ask The Headhunter Newsletter, the truth about equal pay rears its head.

When women get paid less for doing the same jobs men do, the real reason is obvious to any forthright business person, though it seems to elude the media, the experts, and even some women themselves: Employers pay women less because they can get away with it.

The same pundits tell women that they should change their behavior if they want to be paid fairly for doing the same work as men. But the experts, researchers, advocates and apologists are all wrong. There is no prescription for underpaid women to get paid more, because it isn’t women’s behavior that’s the problem.

The same pundits tell women that they should change their behavior if they want to be paid fairly for doing the same work as men. But the experts, researchers, advocates and apologists are all wrong. There is no prescription for underpaid women to get paid more, because it isn’t women’s behavior that’s the problem.

There is only one thing a woman should have to do to get paid as much as a man: her job.

When doing the job doesn’t pay, women of all ages should be aware that younger women today have the solution. According to a recent report from the International Consortium for Executive Development Research (ICEDR), some women have figured it out. Millennial women don’t need to change their negotiating, child-rearing, educational or any other behavior to impress errant employers. They know to quit and move on. This is going to change life at work as we know it.

The myths about women causing their own pay problem

Let’s look at what women are supposedly doing to abuse themselves financially.

We can refer to umpteen surveys and studies about gender pay disparity — and to some that suggest there is no disparity. But a recent Time magazine analysis summarizes the data from the U.S. Census and other sources: “Women earn less than men at every age range: 15% less at ages 22 to 25 and a staggering 38% less at ages 51 to 64.

This has become favorite fodder for the media — and for armchair economists and gender researchers and pundits looking to bang out a blog column. But I think most of the explanations about pay disparity, and the prescriptions for how to get equal pay for equal work, are bunk.

Depending on what you read, women get paid less because they:

- Have kids.

- Interrupt their careers for their families. (See: A stupid interview question to ask a woman.)

- Don’t have the right education (e.g., STEM), so they can’t get good jobs.

- Are nurturing, so they don’t negotiate hard enough for equal pay.

- Don’t like to argue.

- Lack confidence.

- Let their men get away without doing household chores — so those men (if they’re managers) don’t know they should pay women fairly.

These explanations about lower pay are speculation and myth, but the message is always the same: If women would just change some or all of those behaviors, they can shrink the pay gap.

I say bunk. Women don’t cause the pay gap. Employers do. So employers should change their behavior.

The fact

I’ve been a headhunter for a long time. I’ve seen more job offers and observed more salary negotiations than you’ll see in a lifetime. I’ve observed more employers decide what salaries or wages to pay than I can count. And I am convinced the media and the experts are full of baloney about the pay gap between men and women. They are so caught up in producing eye-popping news that they’re doing women a disservice — and confusing speculation with facts.

Here are the facts:

- Employers pay women less to do the same work as they pay men.

Well, there’s just one fact, and that’s it.

Women don’t make themselves job offers, do their own payroll, or sign their own paychecks. The gender pay disparity is all — all — on employers, because we start with a simple assumption: A job is worth $X to do it right, no matter who does it. It’s all about getting the work done. And the employer decides whom to hire and how much to pay.

Here’s the hard part for economists and experts to understand: Employers decide to pay women less, simply because they can get away with it. The law of parsimony instantly leads us to the obvious motive: Paying less saves companies money. Everything else is speculative claptrap.

A review of the bunk

Let’s look at some of the gratuitous “analysis” about why women are paid less than men. Look closely: It all delivers one absurd message: Women are the problem, so women should change their behavior.

Glassdoor, the oft-reviled “employer review” website, reports that overt discrimination may be part of the cause of gender pay discrepancies (Demystifying the Gender Pay Gap: Evidence from Glassdoor Salary Data). But, claims Glassdoor’s economist, Dr. Andrew Chamberlain, “occupation and industry sorting of men and women into systematically different jobs is the main cause.”

“Sorting?” Armchair apologist Chamberlain is saying women apply for jobs that pay less and men apply for jobs that pay more. While this may sometimes be true, what he fails to note is that when a man and a woman do the same job in the same industry, one is paid less because the employer pays her less. The absurd prescription for women: This will change if only women will change their behavior!

Then there’s the HuffPo, in which Wharton researcher Bobbi Thomason says that to fix the gender pay gap, “We need to have men getting involved at home with childcare and other domestic responsibilities.”

Gimme a break. Women, when you get men to wash dishes, you’ll change how boss men pay female employees. The prescription: It’s all up to you. Change your behavior at home.

The Exponent, reporting on Purdue University’s Equal Pay Day event on April 12, says that the wage gap is “largely based on the fact that, generally, women don’t negotiate their salary once they get into their career field.” Those women. Dopes. They’re doing the wrong thing — that’s why they get paid less! Change your behavior!

Kris Tupas, treasurer of the American Association of University Women chapter at Purdue, explains that employers pay women less “because our culture teaches women to be polite and accept what they’re given.” Again the prescription is for women: Change your behavior!

Linda Babcock, a professor at Carnegie-Mellon, wrote a book that explains women’s fundamental problem: Women Don’t Ask. Says Babcock’s book blurb:

“It turns out that whether they want higher salaries or more help at home, women often find it hard to ask. Sometimes they don’t know that change is possible — they don’t know that they can ask. Sometimes they fear that asking may damage a relationship. And sometimes they don’t ask because they’ve learned that society can react badly to women asserting their own needs and desires.”

Women get paid less because they don’t know they can ask! Gimme another break! And what’s Babcock’s prescription? Women — you have to ask to be paid fairly! Change your behavior!

Fox News’s Star Hughes-Gorup tells women how they can fix the pay gap: “Get educated.” If you want to make as much as the guy in the next cubicle who’s doing the same job, hey, get more schooling after the fact to impress your employer.

Next, says Hughes-Gorup, “Embrace asking for help.” Yep — if you learn how to ask properly, you can “start the conversation” about money. In time, you’ll be worth more. She sums it up: “I believe true progress will be made when we acknowledge that the real issue deterring women from talking about money is not confidence, but self-imposed limitations in our thinking.”

The prescription: Women: If you stop limiting your thinking, you’ll get paid more. So, get with it! Change your behavior and your thinking!

Disclosure: I can’t believe anyone buys any of this crap, much less that anyone else publishes it uncritically.

Millennial women have the solution

Why do all those articles prescribe that women must change their behavior to get paid more, when it’s employers who are making the decision to pay them less? Should women appease employers, or respond to unfair pay some other way?

Surveys over the years show that the top reasons people quit their jobs include (1) dissatisfaction with the boss, and (2) work-life balance. (E.g., Inc. magazine’s 5 Reasons Employees Leave Their Jobs.) Money is not the main reason.

But something has changed — especially for Millennial women. Lauren Noël, co-author of a report from the International Consortium for Executive Development Research (ICEDR), says, “Our research shows that the top reasons why [Millennial] women leave are not due to family issues. The top reasons are due to pay and career advancement.”

The report itself quotes women under thirty saying that the number one reason they quit is, “I have found a job that pays more elsewhere.”

What’s interesting is that the HR executives Noël surveyed don’t get it — HR thinks “that the top reason why women leave is family reasons.” Is it any wonder employers attribute lower pay to the “choices” women supposedly make?

The Millennial answer to lower pay

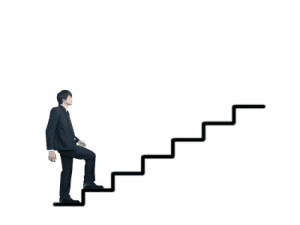

Millennial women are the generation that has figured out they’re not the problem. Unlike their older peers, they’ve figured out that when they’re not getting paid what they want, the answer is to quit and go work for an employer who will pay them more.

As a headhunter, I know first-hand that quitting is the surest way to take control when you’re underpaid and your employer will not countenance paying you fairly. I also realize that not all women — or men, for that matter — can afford to quit a job that is paying them unfairly. But that doesn’t change the answer that will most enduringly change how employers behave.

Kudos to women who take the initiative, and who don’t blame themselves or alter their own behavior when an employer’s behavior is the problem. I wonder how many employers have taken notice? Do they realize the generation of female workers that’s coming up the ranks isn’t going to tolerate financial abuse — they’re just going to walk?

Do we need a law?

Do we need a law?

I’m not a fan of creating laws to dictate what people should be paid. But I’m not averse to regulations about transparency and disclosure. With some simple disclosure regulations, I think more women can start getting paid as much as men do for the same jobs.

Companies want our resumes; let’s have theirs, too — a standard “salary resume” provided to all job applicants, comparing pay for women and men at a company. Employers would be free to pay men twice what they pay women, if they want. And upon checking the salary disclosure, job seekers would be free to walk away and join a competitor who pays fairly for work done by anyone.

Let’s get over it: Women who do the same work as men aren’t the problem. Employers who pay unfairly are, and let’s face what’s obvious: They do it because they can get away with it. (For a story about an employer with integrity, see Smart Hiring: How a savvy manager finds great hires.)

If we’re going to analyze behavior, let’s analyze employers’ underhanded behaviors — not women’s personalities, cognitive styles, or biological characteristics. I’ll say it again — There is only one thing a woman should have to do to get paid as much as a man: her job.

Employers who don’t pay fairly will stop getting away with it when they’re required to tattoo their salary statistics on their foreheads — so job applicants can run to their competitors. Or, more likely — since new laws aren’t likely — employers will change their errant behavior when a new generation of women just up and quits. That would be quite a news story.

Employers who don’t pay fairly will stop getting away with it when they’re required to tattoo their salary statistics on their foreheads — so job applicants can run to their competitors. Or, more likely — since new laws aren’t likely — employers will change their errant behavior when a new generation of women just up and quits. That would be quite a news story.

Maybe then the media and the experts will stop blaming women for the gender pay gap — and start challenging employers to raise their standards.

(Considering quitting? See Parting Company: How to leave your job.)

What’s the solution? Do we need a walk-out? Do we need regulations? Do we need a corporate stock and pillory? Does anybody think there’s no gender pay gap?

: :

I manage a small team, but I’m pretty new to management. Now that it’s time to promote someone, I’m not happy with the criteria my HR department has given me to justify the promotion. It’s frankly nonsense. I don’t want to promote someone just because they’ve been on the job for two years. I want to use the opportunity to really assess whether they are ready for more responsibility and some new authority, and to help the employee realize what this means for them, for my department and for our company. Do you have any suggestions for how I should handle this so it will mean something?

I manage a small team, but I’m pretty new to management. Now that it’s time to promote someone, I’m not happy with the criteria my HR department has given me to justify the promotion. It’s frankly nonsense. I don’t want to promote someone just because they’ve been on the job for two years. I want to use the opportunity to really assess whether they are ready for more responsibility and some new authority, and to help the employee realize what this means for them, for my department and for our company. Do you have any suggestions for how I should handle this so it will mean something? Instead of just turning down my counter-offer and staying at $80,000, which I would’ve gladly taken, they rescinded the offer completely. The hiring manager wouldn’t even respond to my calls or e-mails, even after he said he’d be glad to discuss any questions.

Instead of just turning down my counter-offer and staying at $80,000, which I would’ve gladly taken, they rescinded the offer completely. The hiring manager wouldn’t even respond to my calls or e-mails, even after he said he’d be glad to discuss any questions. Nick’s Reply

Nick’s Reply Today (March 1) we’re joined by some special guests! A big welcome to IT professionals from

Today (March 1) we’re joined by some special guests! A big welcome to IT professionals from

If I get this job — and even with help it’s still a big IF, — it will be my last job. The salary and perks will get me through my last 20 years before retirement, and a few years in, I can even move anywhere I like in the world and work remotely. Sweet.

If I get this job — and even with help it’s still a big IF, — it will be my last job. The salary and perks will get me through my last 20 years before retirement, and a few years in, I can even move anywhere I like in the world and work remotely. Sweet.

I just sent one, after talking to the top dog. I repeated that I am interested in the position and told him of my immediate schedule. More importantly, and motivated by your columns, I told him about some activity of a standards committee that might have a strategic impact on his operations. I said I would be joining the committee, ex officio, by contributing some research I was doing, and I also told him what my input would be if I were working for him.

I just sent one, after talking to the top dog. I repeated that I am interested in the position and told him of my immediate schedule. More importantly, and motivated by your columns, I told him about some activity of a standards committee that might have a strategic impact on his operations. I said I would be joining the committee, ex officio, by contributing some research I was doing, and I also told him what my input would be if I were working for him.