WWEJSS, LLC — a.k.a. SevenFigureCareers — is a “recruiting” company that does not legally exist, yet major credit card companies have authorized merchant accounts that it uses to fraudulently collect fees for services it never delivers, while it silences its victims with a confidentiality agreement that’s fake, too.

A credit card scam

A credit card scam

In a series of recent articles, readers shared their experiences with phony recruiters at SevenFigureCareers (a.k.a. 7F, 7figcareers, and loads of other names) who scammed job seekers out of loads of money:

But, how does a racket like SevenFigureCareers get a merchant account to collect fees via American Express, MasterCard and VISA — then win disputes when victims complain about being scammed?

By getting victims to sign a contract.

To defend against claims of fraudulent credit card charges, 7F tells credit card companies that its “customer” signed a contract and that 7F delivered what it promised under the contract — hence, no refund is due.

One victim, John Rice (not his real name), told me that AmEx said it was a contractual problem between him and 7F because 7F reported it had fulfilled its obligations. AmEx suggested he hire a lawyer after AmEx rejected four requests for a refund.

After reports detailing the scam appeared on this website, AmEx eventually refunded Rice and other cardholders thousands in fees collected by 7F, and cancelled 7F’s merchant account. But it seems that AmEx issued that merchant account without confirming whether 7F is a legal entity. AmEx declined to explain exactly how it vets merchants before signing them up. AmEx also won’t disclose what problems it found with 7F after a phony lawyer threatened a user of this website who spoke up about getting scammed.

The SevenFigureCareers contract is a fraud

Two real lawyers reviewed the 7F contract for Ask The Headhunter. One of them explained the problem:

“A contract is between two parties. If there are not two parties, then there is no contract. This contract is invalid because there’s only one party — the victim.”

When high-salary executives don’t recognize that an agreement they’re signing is invalid, then everyone needs to learn the basics.

Read the contract

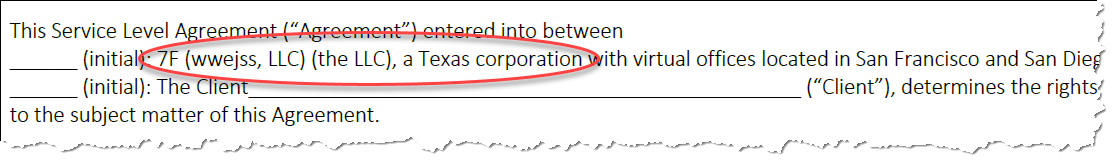

Let’s start with the SevenFigureCareers contract. Several victims provided me with copies. Each seems to be coded with an ID at the upper left, to identify the victim. I’ve redacted that.

Here’s why the contract is a fraud, and why AmEx — and MasterCard and VISA — should never have issued merchant accounts to SevenFigureCareers.

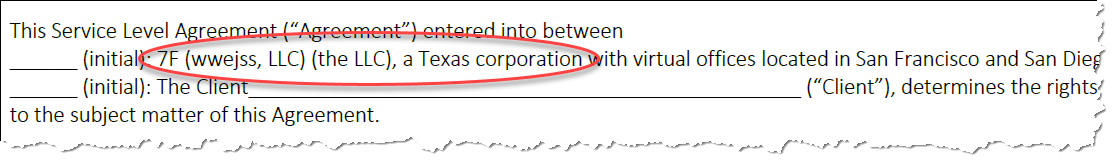

Although it calls itself by many names, SevenFigureCareers does business under a name its victims don’t see until they receive a contract: WWEJSS, LLC. But this “Texas corporation” does not exist. Thus, there is no contract.

Did credit card companies get scammed, too?

So, how does a fake company collect payments through real credit card accounts? Why would credit card companies with anti-fraud departments authorize merchant accounts for crooks? Good questions, for which we have no answers. And that means you should never assume that paying with a credit card protects you from fraudulent vendors.

Did these credit card companies get scammed, too? How? Will they ever admit it?

Tip: If you have concerns about a company you’re about to contract with, investigate the entity. If SevenFigureCareers’s victims had done due diligence, they’d never have gotten suckered. They never would have paid — even with a credit card. John Rice, a seasoned executive, has said to me several times, “I was such a dumb shit.” Yes, he knew better — but he suspended his concerns because he figured American Express would protect him from losses. American Express, however, apparently didn’t take reasonable precautions to protect Rice from this phony merchant.

Caveat emptor really does mean that due diligence is always your responsibility.

WWEJSS, LLC is a fraud

American Express credit card charges from SevenFigureCareers appear as WWEJSS, LLC or WWJESS, LLC on victims’ statements.

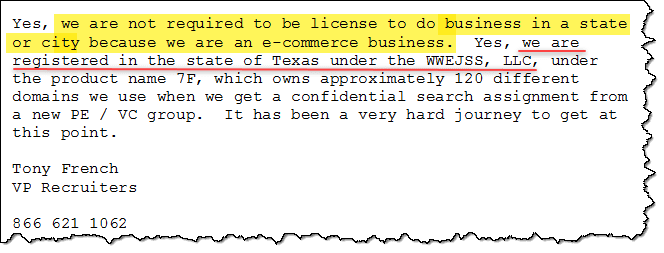

After doing some basic research, one victim learned the company is not licensed in Texas and confronted 7F recruiter “Tony French.” French replied in an e-mail that SevenFigureCareers doesn’t have to be licensed, but that it is registered in Texas under “WWEJSS, LLC.”

On September 29, I contacted the office of the Texas Secretary of State. Victoria, a helpful employee, told me that, “If it’s a legal entity, like a Texas corporation or LLC or limited partnership, it has to be registered with the State, even if it only does e-commerce.”

She then looked up WWEJSS, LLC and WWJESS, LLC, “a Texas corporation,” in the Texas registry.

“There is no WWEJSS or WWJESS registered,” Victoria reported.

That makes Tony French a liar and his “company” illegal.

Hunting… scammers, or deer?

Hunting… scammers, or deer?

Nor is there a registration for SevenFigureCareers, Seven Figure Careers, 7Figures, or any other such name. (In 1993, “Seven Figure, Inc.” was registered to Carl Poston, but that expired in 1996.)

There is, however, a registration for 7F, Inc. — to Gary Benbow in Yoakum, Texas. I spoke with Gary, who runs the respected 7F Whitetails Ranch. The 7F comes from an old cattle brand that’s been in his family for generations. He’s never heard of SevenFigureCareers. Gary’s not in the recruiting business. His family raises cattle and offers trophy deer hunting on the property. And he’s not happy about scammers tarnishing his registered brand.

Targeting the credit card companies

American Express and other credit card companies have permitted an unregistered legal entity to collect payments with their credit cards even after the victims gave notice that this merchant is a fraud. Apparently, AmEx failed to do the simplest due diligence. (When I asked, AmEx would not disclose exactly how it vets its merchants.) Then AmEx rejected requests for refunds out of hand, relying on what we now know is an invalid contract used by a fake company operating illegally in Texas.

These credit card companies have put a target on their own backs that says “Fraud.” I didn’t ask Gary Benbow whether he takes credit cards. But I’m sure he’d love to find the guys who call themselves 7F.

As of the date of this column, Texas Company Search lists no registrations for any of the SevenFigureCareers legal entities — least of all WWEJSS, LLC, the name listed on its contracts.

WWEJSS: How it silences its victims

It seems clear that WWEJSS has flourished because it keeps its victims quiet.

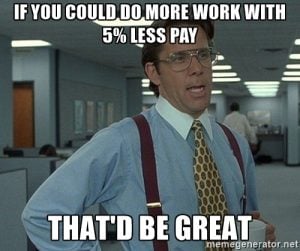

After John Rice’s credit card dispute was rejected, he posted about the scam on this website. Within minutes, SevenFigures silenced Rice with an e-mail. A phony lawyer “representing” SevenFigures threatened him with a contractual penalty of $25,000 if he didn’t remove what he posted. It was actually that threat that publicly unraveled the entire SevenFigureCareers scam.

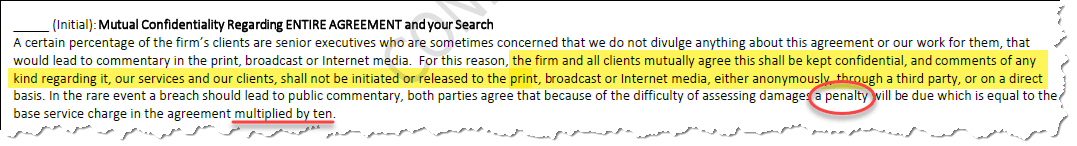

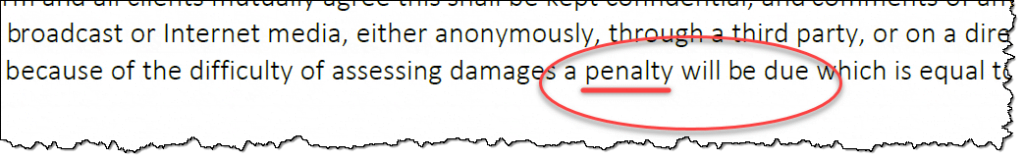

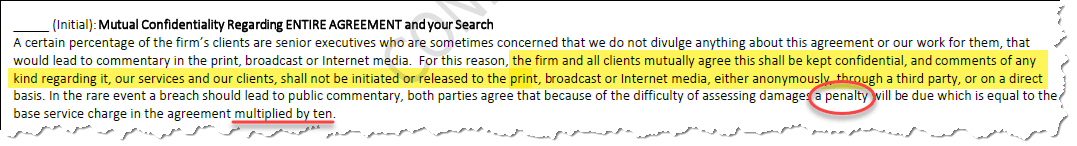

What scared Rice and other victims into silence is an intimidating non-disclosure clause (or NDA, or Non-Disclosure Agreement) in the contract — “Mutual Confidentiality Regarding ENTIRE AGREEMENT and your Search.”

The NDA threat

We’ll forget for a minute that the entire contract is invalid because WWEJSS doesn’t exist. Let’s take a look at what these people agreed to — and at what a lawyer says about it.

This clause essentially says that the signer can’t reveal anything about their experience with 7F, or comment about it anywhere to anyone. Victims I interviewed were convinced that, even if they knew they’d been scammed, they’d have to pay 7F $25,000 if they told anyone.

But, this section of the contract by itself wouldn’t stand up in court, say two attorneys who reviewed it. That is, it seems there is no danger to SevenFigures’ victims if they tell all to the world. (Note: The opinions of the lawyers I spoke with are not legal advice. If you have a specific contractual controversy, you need to get advice from a lawyer about your specific problem.)

Phony Lawyering: liquidated damages & penalties

It’s worth understanding a legal concept that’s key to many contracts. The idea is pretty simple. If we bind ourselves with a contract, and I do something that violates our contract, I will cause you damage, and I must reimburse you for that damage.

But, how much could the damages be worth? The law acknowledges this can be hard to calculate. Here’s how one lawyer explains it:

In situations where it’s not practical or maybe possible to come up with an actual number, in a contract parties can “pre-decide” what the damages will be (called liquidated damages), but there has to be a reasonable relation to the actual harm caused. It can’t just be some outlandish number like a bazillion dollars because then that would be more like a “penalty” and less like compensation for actual damages received.

If a court (judge) feels like the amount pre-decided (the liquidated damages) is actually a penalty then they may decide to throw out that figure. That is why lawyers go to great lengths when using a liquidated damages clause to make it seem as far from a penalty as possible, starting with not calling it a penalty!

In this lawyer’s opinion, the fact that the contract calls the payment a “penalty” would probably invalidate any damages claim. What this — along with the other sloppy wording and writing in this “contract” — tells us is that a lawyer didn’t write it.

In this lawyer’s opinion, the fact that the contract calls the payment a “penalty” would probably invalidate any damages claim. What this — along with the other sloppy wording and writing in this “contract” — tells us is that a lawyer didn’t write it.

My guess is it was written by the same putz who impersonated a lawyer — illegal in all 50 states — in the e-mail threatening John Rice.

This is how 7F silences its victims, using an unenforceable confidentiality agreement in a fraudulent contract to intimidate them into keeping their mouths shut. They naturally worry that speaking up would cost them $25,000 for violating confidentiality. But liquidated damages normally can’t be a penalty — only compensation for damage.

Go suck rocks.

All that Tony French’s victims have to do is tell him to go suck rocks when he threatens them. And that’s why we’re having this brief legal lesson, courtesy of two friendly lawyers who hate scammers.

(We won’t get into it here, but SevenFigureCareers violated its own NDA when Tony French shared confidential communications from his private equity “clients” with the candidates he was supposedly recruiting. Except those PE clients don’t exist — so where’s the harm?)

Who should sue whom?

Well, it seems Mr. French might be doing more than sucking on rocks soon.

I asked Lawrence Barty, a retired attorney who has specialized in employment and labor law, for his views on this case. He suggests the SevenFigureCareers victims may have grounds to sue whoever is behind this phony recruiting firm. Even though SevenFigureCareers doesn’t legally exist, someone convinced the victims that the firm does exist and that the contract is real. And that person faces trouble.

The persuasion of this “person” led you into a situation in which you lost money. If you have a legal claim, it can’t be against an entity that doesn’t exist — right? So who can you sue?

If you can identify the person who perpetrated this fraud, a tort claim of fraudulent inducement might be possible (as always, State laws vary) against that person — not against the illusory 7F. You were induced by X (identity presently unknown) to enter into a contract that cost you money, but was known in advance by X to be worthless. So, you should sue X, the person who tricked you into entering that contract. A claim of that type can be a tort claim, possibly giving rise to compensatory and punitive damages.

Ah. Now we get to penalties. Not just compensatory damages, but punitive damages. Except now the penalty is against the scammer.

This is tricky stuff — maybe more than your readers need to know. The threshold issue is to identify and locate who is behind 7F. You can’t sue someone whom you can’t identify. And, because he is a crook by any definition, he therefore is likely to be a very, very elusive target.

Yah — like a deer on Gary Benbow’s ranch.

What’s next?

Since this series about SevenFigureCareers.com was published, the “firm’s” website has gone dark. Many of the associated phony websites of phony private equity and venture capital firms have disappeared. But SevenFigureCareers continues to operate and collect fees, with a web presence on Manta, a business web-hosting service. It’s newest customers have been in touch with Ask The Headhunter — after they lost their money.

Where is the crook? Has American Express found him?

How does someone running a fake company get merchant accounts with American Express, VISA and MasterCard? What basic controls against fraud do these credit card companies have in place? I mean — how hard is it to look up a corporation’s or LLC’s credentials? A dog with a note in its mouth can do it.

In the next edition, we’ll go down to the bottom of this wormhole: Who’s behind the SevenFigureCareers recruiting scam?

Are you one of the victims scammed by SevenFigureCareers? Or did you see the scam coming and walk the other way? How would you avoid getting fleeced by a “career service?” What due diligence do you do?

: :

Well, you decline to answer, hang up, and chalk up another company you’d never dare to work for. In other words, you discriminate.

Well, you decline to answer, hang up, and chalk up another company you’d never dare to work for. In other words, you discriminate.

Question

Question Most professional associations have “X helping X” groups (e.g., lawyers helping lawyers). These groups consist of people being rehabilitated from disabilities of one sort or another (including a number of recovering alcoholics). It never hit me before, but such groups can be great sources of hires. When we brought our latest aboard and she worked out extremely well, I asked where we found her. I got to thinking after that.

Most professional associations have “X helping X” groups (e.g., lawyers helping lawyers). These groups consist of people being rehabilitated from disabilities of one sort or another (including a number of recovering alcoholics). It never hit me before, but such groups can be great sources of hires. When we brought our latest aboard and she worked out extremely well, I asked where we found her. I got to thinking after that.

A credit card scam

A credit card scam

Hunting… scammers, or deer?

Hunting… scammers, or deer?

In this lawyer’s opinion, the fact that the contract calls the payment a “penalty” would probably invalidate any damages claim. What this — along with the other sloppy wording and writing in this “contract” — tells us is that a lawyer didn’t write it.

In this lawyer’s opinion, the fact that the contract calls the payment a “penalty” would probably invalidate any damages claim. What this — along with the other sloppy wording and writing in this “contract” — tells us is that a lawyer didn’t write it. HR came to me and discussed an opportunity that I might be interested in. However, instead of hiring someone else, HR proposed to my boss that he offer me this position while I keep my current position. It’s basically a dual role — two jobs.

HR came to me and discussed an opportunity that I might be interested in. However, instead of hiring someone else, HR proposed to my boss that he offer me this position while I keep my current position. It’s basically a dual role — two jobs. How to Say It

How to Say It SevenFigureCareers

SevenFigureCareers I asked John if he’d called the lawyer. Of course, he said. He left a voicemail because no one answered — but the lawyer never called him back.

I asked John if he’d called the lawyer. Of course, he said. He left a voicemail because no one answered — but the lawyer never called him back. Earlier today the SevenFigureCareers.com website was altered. The 7F logo is gone as is much of the promotional verbiage. Most of the site is now locked down behind passwords. If you type the URL into your browser, the site comes up. But if you click a link to get there, the site yields a blank page with “Nope” in a box at the top. (But if you then put your cursor at the end of the URL in your browser and hit Enter again, the site comes up.) It seems they are trying to avoid inbound links from other sites — like from this article.

Earlier today the SevenFigureCareers.com website was altered. The 7F logo is gone as is much of the promotional verbiage. Most of the site is now locked down behind passwords. If you type the URL into your browser, the site comes up. But if you click a link to get there, the site yields a blank page with “Nope” in a box at the top. (But if you then put your cursor at the end of the URL in your browser and hit Enter again, the site comes up.) It seems they are trying to avoid inbound links from other sites — like from this article. If there’s any change, we donate it to an animal shelter.) The sooner you appear with a dog, the bigger the bonus you’ll earn — up to $1,000.

If there’s any change, we donate it to an animal shelter.) The sooner you appear with a dog, the bigger the bonus you’ll earn — up to $1,000. The U. S. Department of Labor

The U. S. Department of Labor Employers are so out of it that they’re not only putting up digital roadblocks against people they’re trying to attract — such as online application forms and

Employers are so out of it that they’re not only putting up digital roadblocks against people they’re trying to attract — such as online application forms and  This cannot be reconciled with the idea that an employer is trying to attract you. When you’re an abstraction in a database — a mess of keywords — the assumption is that you’re to be avoided and feared, either as a waste of time or, in this case, as a physical threat.

This cannot be reconciled with the idea that an employer is trying to attract you. When you’re an abstraction in a database — a mess of keywords — the assumption is that you’re to be avoided and feared, either as a waste of time or, in this case, as a physical threat. Question

Question