In the May 1, 2012 Ask The Headhunter Newsletter, an employer is out $6,000 when a new hire found through an agency jumps ship after 15 days. Can the employer charge the next employee for quitting?

We recently hired an employee using an agency through which he was temping for us. We paid the temp agency a fee of $6,000 (20%) of the person’s salary. After 45 days, the new employee resigned to move out of state. The temp agency says that he was here for more than 15 days, so they are not going to do anything about their fee.

We have a policy for encouraging continuing education. If an employee in good standing wants to take a course or go back to school at night or weekends, we will pay 70% of the costs, providing successful completion of the courses. If the employee leaves before two years, the employee must reimburse our company for the education expenses.

Because of this disagreeable experience with the agency, we are contemplating a similar policy: “If you leave before your second anniversary, you will need to reimburse some portion of the headhunter fee.”

What are your thoughts on this approach? It would make us feel more confident about using a placement service. Thank you in advance for your thoughts.

My Advice

Suppose you hired that employee without an agency’s involvement, and he quit after 45 days. Would you require him to refund part of the salary you paid him?

Of course not. Yet that’s what you’d be asking someone to do if you hired him through an agency: To pay you back out of their salary. Did you pay a fee to the employee so he’d come work for you? Of course not. So there’s nothing for the employee to refund.

(I’m not a lawyer, but my guess is it would be illegal for you to take back salary because someone quit a job.)

The agency, on the other hand, earned a fee for finding an employee for you. It’s up to you to work out a reasonable contract and financial arrangement with the agency, for the work it does for you (recruiting). The underlying problem is that you as the employer make the hiring decision — not the agency. The agency’s job is to deliver viable candidates. It’s duty ends there, or after some agreed-upon guarantee period. I don’t think any agency would guarantee a placement for two years, one year, or even six months.

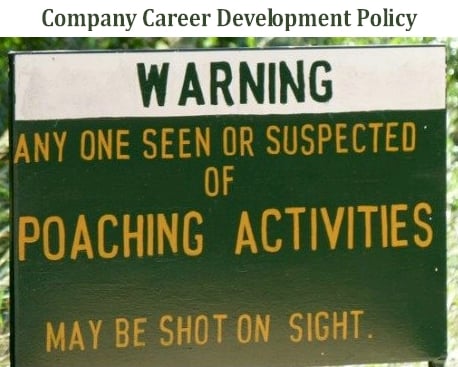

I don’t like your idea at all because you’re making the employee responsible for your contract with the agency.

So what are your options as an employer? Let’s start with typical placement agreements, though of course they vary greatly. Commonly, a headhunter’s (or recruiter’s, or agency’s) fee is about 20% of the employee’s starting salary. Please note: The fee is not deducted from the employee’s pay. It’s merely calculated based on that salary. So it’s an additional cost to the employer. Employers that routinely use external recruiters usually budget for such fees. Negotiate the best fee you can.

It’s common for temporary placement agency agreements to permit you to change from “temp to hire” — that is, to hire the temp permanently. The fees and any guarantee period should be spelled out in the contract. To control your costs, you might negotiate a permanent placement fee that is progressively lower based on how long you’ve already been paying temp fees to the agency for that particular employee.

Whether it’s a temp agency or a headhunter you’re working with, the contract usually includes a guarantee period. Many recruiting firms offer guarantees for between 30-90 days. (Some offer no guarantee at all.) If the new hire “falls off” in that time, the agency will either replace the hire, or refund a prorated portion of the fee, or the fee is refunded completely. I’ve never heard of a 15-day guarantee period. It seems too short to be meaningful. But if that’s what you agreed to, it was your choice.

You might be able to negotiate a more aggressive refund guarantee with recruiters. Please keep in mind that it’s pretty unusual for a new hire to leave so quickly. (If it happens to you often, then you’ve got another problem!) Check a recruiter’s (or agency’s) references: Do they have a reputation for placements quitting early?

I want to caution you about charging placement fees back to your employees. If it’s not illegal, I think it’s unethical. It comes out of the employee’s salary, but (unlike education) the employee gets nothing in the bargain. I suggest you work this out with your agency or headhunter instead.

Has an employer ever charged you to quit your job? If you’re an employer, have you ever recovered a placement fee from a departing employee? Headhunters: How do you handle “fall offs?” How long is the typical “guarantee” on a placement?

: :