In the January 29, 2019 Ask The Headhunter Newsletter we consider the implications of a stunning Wall Street Journal investigation of Glassdoor “company reviews.”

What is Glassdoor serving its customers?

What is Glassdoor serving its customers?

A Wall Street Journal investigation suggests that Glassdoor is selling cooked “company reviews.”

“Jennifer Peatman, who headed Roostify’s human-resources team…asked human-resources staffers on her team to post new reviews on Glassdoor, hoping to offset the negative ones.”

“Concerned that negative reviews could hurt recruiting, Guaranteed Rate CEO Victor Ciardelli instructed his team to enlist employees likely to post positive reviews…”

“…companies, including Guaranteed Rate, have pressured employees to write positive reviews in order to raise poor ratings.”

Glassdoor is owned by Recruit Holdings Co., Ltd., based in Tokyo, Japan.

Can millions be wrong?

Still largely unregulated, leading recruitment advertising companies like LinkedIn, Indeed, ZipRecruiter and Glassdoor, among others, imply their services deliver benefits that no rational person believes are possible — while job seekers nonetheless swarm those sites like flies drawn to the nutritious scent of dung.

The job-searching and recruitment advertising models that these multi-billion-dollar companies market to employers and job seekers alike have created a smelly air in the job market. ZipRecruiter eliminates the “hassle” of recruiting and makes hiring “easy” — but Inc. magazine revealed it was selling illegal job ads. LinkedIn “connects” people to jobs through automated mails that deliver unsolicited job leads — that a federal judge called “spam.”

Everyone knows it’s phony marketing. But everyone excuses it as par for the course. And the employment industry banks on this contradiction between what consumers know and what they tolerate.

Hapless users routinely excuse the wild marketing claims and unforgivable sales tactics that now seem to define America’s employment system — which is now embodied in this small handful of online recruitment advertising firms. Frustrated job seekers have become numb to wasting their time and money — because employers openly endorse and participate in a shameful system of recruiting and hiring that challenges credulity.

It’s shocking the law has not come down on employers and an employment industry that together manipulate the information a nation relies on to fill jobs with workers. The latest example is an expose of the leading repository of “company reviews” that job seekers grudgingly rely on when deciding where to go work next.

The cost of questionable salary data

Glassdoor itself is clear in its Terms of Use that it doesn’t stand by anything posted by users or employers — that is, all its salary and company reviews:

“Because we do not control such Content, you understand and agree that: (1) we are not responsible for, and do not endorse, any such Content, including advertising and information about third-party products and services, job ads, or the employer, interview and salary-related information provided by other users; (2) we make no guarantees about the accuracy, currency, suitability, reliability or quality of the information in such Content; and (3) we assume no responsibility for unintended, objectionable, inaccurate, misleading, or unlawful Content made available by users, advertisers, and third parties.”

We’ve discussed the problem of data gathered from anonymous sources before. In Glassdoor Salary Data: Worse than useless we looked at how Wired magazine’s Rachel Nuwer reported a simple test that shattered the myth of Glassdoor’s vaunted salary surveys.

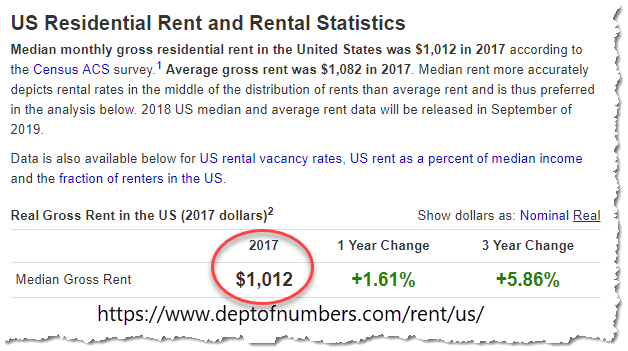

We saw that the “self-reported” salary information published by Glassdoor — if relied upon for salary negotiations — could cost a job seeker an additional 69% worth of compensation, according to Wired. When Glassdoor’s slap-happy anonymous data is compared to rigorously vetted salary data gathered directly from employers, it seems the job applicant stands to lose.

We saw in the disclaimers of the Terms of Use section of the Glassdoor website (see sidebar) that the company admits it publishes what seems to amount to useless crap — not verified, valid, reliable information.

Manipulation of reputations on Glassdoor

Last week, the Wall Street Journal released a damning report that addresses what skeptical job seekers have long been asking: Is wrong information being given out at Glassdoor, the employee feedback site where anonymous people rate the companies they work for?

In cooperation with Columbia University and the University of Washington, The Journal conducted an in-depth analysis of 4.8 million anonymous reviews, about more than 8,500 companies, posted on Glassdoor. The results reveal How Companies Secretly Boost Their Glassdoor Ratings — apparently with Glassdoor’s (Wink, wink! Nod, nod!) help and encouragement. (Please note that the Journal is behind a pay wall.)

Says the Journal: “Glassdoor’s company ratings are a powerful weapon in job recruiting, giving companies an incentive to inflate them.” And inflation is what the analysis found.

The dominant source of company reviews

The Journal points out that “Glassdoor has become an important arbiter of employee sentiment in today’s highly competitive job market. A Wall Street Journal investigation shows it can be manipulated by employers trying to sway opinion in their favor.”

Is that forgivable marketing and public relations, or is it an indictable misrepresentation of Glassdoor’s products to its customers? One HR-related website that commented on the Journal report, BenefitsPRO, said: “The trends threaten to undermine Glassdoor’s credibility as a source for accurate information.”

The power of Glassdoor and its impact on the American job market and economy cannot be underestimated — nor can the import of the Journal’s findings.

“Sought-after workers — the site gets about 60 million users per month, according to web-research firm SimilarWeb — read reviews to help determine where they want to work.”

The article quotes Andy Challenger, vice president of outplacement firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas: “Glassdoor is the most dominant company reviews website by far.”

According to Challenger, poor ratings on Glassdoor can cost an employer dearly, “particularly at a time like right now, with unemployment at historically low levels when companies are fighting to retain and attract good people.”

The Journal found that many employers take special measures to try and manipulate their reputations by “encouraging,” “galvanizing” and “pressuring” employees to post “five-star” reviews. But the question is, what liability does Glassdoor have for it?

No amount of rationalizing (“Well, I take the reviews with a grain of salt, but I rely on them anyway.”) excuses a job seeker’s reliance on company reviews that were prompted by the reviewer’s employer. And when we see how and why those reviews were prompted, Glassdoor’s entire database of reviews takes on the smell of a barrel of fish that includes maybe a few — and maybe a lot — of rotting dead ones.

A concerted conspiracy to manipulate recruiting?

You can and should read the analysis for yourself. But let’s look at the screaming evidence of manipulation behind the “spikes” in five-star company reviews on Glassdoor.

The Journal reports that its analysis “identified over 400 companies with unusually large single-month increases in reviews” that statistically seem to be related to efforts by those companies to boost their ratings on Glassdoor.

Is this a concerted conspiracy to improve recruiting by manipulating companies’ reputations among job seekers? Can a company with serious employee relations problems make itself seem like a sweet place to work by encouraging, pressuring and rewarding “target groups” of its workers for juicing reviews on Glassdoor?

The Journal’s analysis certainly seems to give credence to the imprecation of a famous 1970s poster depicting a fetid dung heap: “Eat Sh#t! 50 billion flies can’t ALL be wrong!”

The Wall Street Journal seems to imply that employers are gaming Glassdoor’s company review system, but the Journal’s analysis actually seems to reveal that Glassdoor is in on the game.

Let’s look at what the Journal tells us.

Which companies are jamming the frammitz?

The Journal delivers details from its analysis of “roughly 8,500 companies with the most Glassdoor reviews” and calls out these specific companies — among 400 it claims had suspicious spikes in their reviews.

- Guaranteed Rate

- Elon Musk’s SpaceX

- SAP

- Slack

- Anthem

- Clorox

- Brown-Forman Corp. (the maker of Jack Daniel’s whisky)

- Bain

- Roostify

What did over 400 companies do to “spike” their reviews?

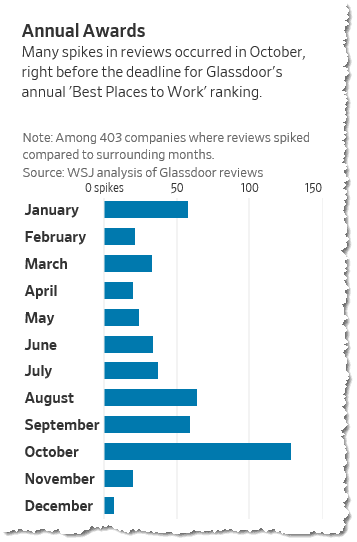

The Journal inquired about how the review spikes occur, mostly around each October, when Glassdoor hands out its “Best Places to Work” awards.

“A Glassdoor spokeswoman said reviews may jump for a variety of reasons, including hiring surges, a company event or internal encouragement.”

Say what? Internal encouragement? Do you mean like this?

- Mortgage broker Guaranteed Rate saw its Glassdoor ratings fall to 2.6 out of 5 last summer. “CEO Victor Ciardelli instructed his team to enlist employees likely to post positive reviews, said a person familiar with his instructions. In September and October these employees flooded Glassdoor with hundreds of five-star ratings. The company rating now sits at 4.1.”

- Among the companies with large spikes, “Spokespeople for Slack, LinkedIn and Anthem said their companies have encouraged employees to give feedback.”

Best time for review “spikes”

The investigation revealed that reviews “balloon” around the annual October deadline for Glassdoor’s Best Workplaces award.

The investigation revealed that reviews “balloon” around the annual October deadline for Glassdoor’s Best Workplaces award.

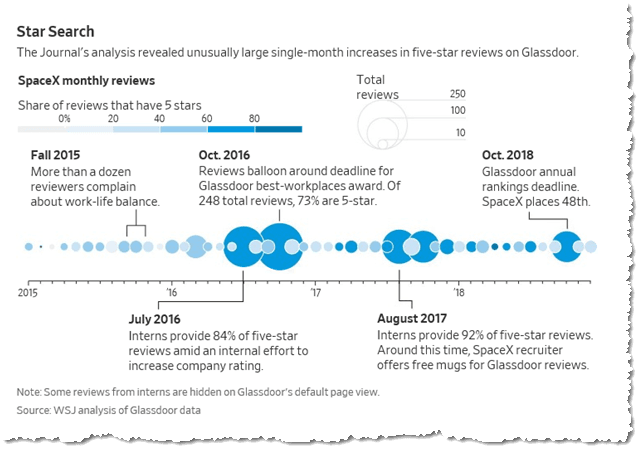

- “Of 248 reviews [for one company at awards time], 73% are 5-star.”

- “In some cases, companies have encouraged loyal employees to post reviews as part of a publicity campaign. SpaceX and SAP, for example, galvanized employees to leave reviews to make Glassdoor’s annual ranking of the ‘Best Places to Work.’”

But any time is a good time “to raise poor ratings”:

- “Other companies, including Guaranteed Rate, have pressured employees to write positive reviews in order to raise poor ratings, according to interviews with current and former employees.”

- In some cases, the disclosures by top executives are astonishing: “Guaranteed Rate’s Mr. Ciardelli said in a written statement that his management team felt Glassdoor ratings didn’t accurately reflect the company’s work environment and so it asked employees to post reviews.”

What employees would actually agree to post 5-star reviews on demand? Glassdoor told the Journal that “it coaches clients on how to target groups that tend to be more enthusiastic, such as new hires, according to guidelines for employers posted on its site.”

- “Interns provide 92% of five-star reviews.”

Glassdoor “coaches clients” to “target” employees most likely “to be more enthusiastic.” Wink, wink. Nod, nod. Do you believe Glassdoor is a passive participant in five-star “spikes?”

Hey – No free mugs!

How’s this for clean hands:

“Glassdoor warns companies not to coerce employees to post positive reviews or to incentivize them to do so with money or prizes.”

Yes, but:

- “In the summer of 2017, SpaceX recruiter Brittany Jacobson sent emails encouraging employees to post reviews in order to make Glassdoor’s ‘Best’ list, said a person familiar with the effort. Workers were offered free SpaceX mugs for completing their review, said the person.”

Check the July 2016 and August 2017 “bubbles” in SpaceX’s monthly reviews:

Glassdoor’s warnings, employers’ branding campaigns, and rewards for employees to post five-star reviews collide while Glassdoor seems to turn a blind eye.

- “SpaceX employees flooded Glassdoor with 180 five-star reviews in October 2016. In most months that year, it earned less than a dozen five-star reviews.”

- “Some months with high numbers of reviews came after interns were recruited, according to the first person familiar with the effort. They provided more than 84% of five-star reviews in July 2016 and in August 2017.”

Who pulled off this 15X increase in 5-star reviews at SpaceX?

Do you know where to list accomplishments on your resume?

- “Ms. Jacobson took credit for the campaigns on her LinkedIn profile, writing that she executed ‘company-wide employer branding campaigns’ on Glassdoor, increasing the number of reviews by more than 1,000, raising the company’s overall rating to 4.4 stars from 3.8 and resulting in SpaceX landing on Glassdoor’s ‘Best’ list two years in a row.”

What a great resume! When the Journal tried to contact her, “Ms. Jacobson didn’t respond to requests for comment. She removed the reference to Glassdoor on her LinkedIn page in mid-December after being contacted by the Journal.”

“A company spokeswoman said [SpaceX’s human-resources chief, Brian] Bjelde didn’t sign off on gifts in exchange for reviews or ask for positive reviews.”

Oops. Forget you ever heard about those free mugs. It seems Glassdoor did.

Does Glassdoor do anything to prevent “spikes” in 5-star reviews?

Glassdoor’s spokeswoman told the Journal that “Suspected ‘ballot box stuffing’ could…cause Glassdoor to remove positive reviews” so “The company touts a combination of human moderators and technology filters to detect attempted abuse.”

The Journal suggests Glassdoor isn’t alone. Other sites that rely on user reviews for their existence also “face” problematic review practices.:

“Glassdoor’s problem echoes the challenges faced by other online rating platforms, which are trying to ensure their rankings are real. Amazon.com Inc., local-business site Yelp Inc. and hotel-and-restaurant site TripAdvisor Inc. have all had to fend off attempts to game reviews and ratings.”

But there’s no mention of what measures Glassdoor has in place to maintain the integrity of reviews. If Glassdoor is the innocent while its corporate customers are gaming it, then how does the Journal explain this?

- “Glassdoor charges companies to customize their pages and promote open jobs, from a few hundred dollars to tens of thousands of dollars a month. Paying customers can feature a glowing review at the top of their page, prevent rival companies’ jobs from appearing…”

How does the Journal explain taking money to boost an employer’s reputation?

Is Glassdoor encouraging “spikes” in 5-star reviews?

It would seem so, suggests the Journal:

- “Each year, Glassdoor drives traffic-and a flood of reviews-to its site by ranking hundreds of companies and CEOs in the U.S. and four other countries.” This is Glassdoor’s “Best Places to Work” ranking. Could that be Glassdoor’s way of (Wink, wink! Nod, nod!) encouraging its customers to cause sudden spikes in their company ratings?

And it gets worse. One wonders just how explicit Glassdoor would have to be, before the Federal Trade Commission were to investigate the connection between Glassdoor’s site traffic and revenues, and the company’s promotion of its Best Places to Work contest that encourages spikes in 5-star reviews:

- “Glassdoor said its algorithm ranks the companies based in part on the quantity of reviews in the past year, as well as ‘what employees have to say that shows winners truly outshine the rest.’”

- “According to the Journal’s analysis, more than a quarter of spikes came in October — right around the deadline for Glassdoor’s annual ranking.”

Do 5-star reviews pay off?

You bet.

After employees posted complaints about Guaranteed Rate’s “management, pay and long work hours, the company’s rating dropped to 2.6 from 3.5. “The approval rating for Mr. Ciardelli, the CEO, plummeted to 43% from about 75%”

After employees received an e-mail that read, “Please complete a Glassdoor review with a strong five-star rating for us,” Ciardelli’s approval rating almost doubled — to 83%. “Dozens of glowing reviews were written by people who listed their title as managers.”

Is it time for an award?

What does this mean for job seekers?

Millions of job seekers swarm Glassdoor for salary data and “reviews” of employers, seemingly convinced that millions of Glassdoor users — including employers and HR professionals — can’t possibly be wrong.

But the Wall Street Journal’s investigation of Glassdoor’s and employers’ practices has revealed a stink unrivaled in the employment industry.

The only prudent conclusion one can draw from the Journal’s analysis of millions of reviews about over 8,500 companies on Glassdoor is that Glassdoor is crack for Human Resources departments that need a powerful stimulant to make their corporate reputations feel better — at any cost.

The Journal seems to have revealed a pervasive public relations manipulation whose objective is to game reputations.

Say what??

Say what??

Perhaps not surprisingly, a search of the websites of a dozen leading HR associations one week after publication of the Journal’s report doesn’t turn up any articles about it.

Notably, SHRM (the Society For Human Resource Management) seems to have posted nothing about the matter.

Glassdoor itself has published no response or comment on its website, and does not list the Journal’s article on the “Here’s what others are saying about us” section.

Glassdoor is in business to generate as much site traffic and revenue from employers as it possibly can. Absent regulations that would force the company to validate the data it sells, and to refrain from tacitly and explicitly permitting, encouraging and rewarding its customers for gaming Glassdoor’s ratings system, job seekers have no reason to expect Glassdoor can or will help them make sound decisions about where to work or how to negotiate job offers.

The shocking failure of Glassdoor to ensure the validity and reliability of information it sells to employers and job seekers alike reveals a business model run amuck amidst gullible — nay, stupid — users who really, really want to believe they cannot seek out honest, legitimate information about the reputations of employers on their own. Why do the work, when automation will deliver answers for a price?

There are three clear lessons in the Journal’s investigation and analysis for any prudent business person who depends on valid, reliable data and information to make sound judgments:

- The chance that any information found on Glassdoor is dishonest is much greater than zero. In fact, based on the Wall Street Journal’s investigation, it is more likely than not that information being given out at Glassdoor is dangerously tainted if not simply wrong.

- No one — not employers and not job seekers and not any company’s employees — needs the anonymously generated, unaccountable information Glassdoor sells, because it is too likely to be worthless or dangerous, and too likely to distract people from the all-important task of making their own sound judgments based on real interactions with other people who are personally accountable.

- The business world — especially the HR profession — doesn’t think there’s really anything wrong with what the Journal found.

Do you buy what Glassdoor is selling? How do anonymous company reviews affect employers, job seekers, the job market and our economy? Does anybody care — or is this just the way it’s going to be?

: :

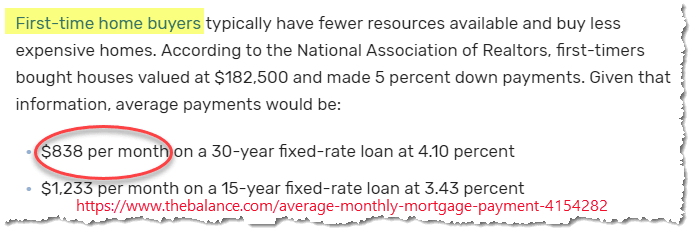

I’m a Senior Data Scientist and I just got a job offer, but the salary is about $1,000 lower than I expected. It’s a management position with less than a dozen staff reporting to me. They also offered a very generous signing bonus of about $50,000.

I’m a Senior Data Scientist and I just got a job offer, but the salary is about $1,000 lower than I expected. It’s a management position with less than a dozen staff reporting to me. They also offered a very generous signing bonus of about $50,000. I operate three restaurants. It’s getting harder and harder to hire workers. People just don’t want to do this kind of work any more, but for young people it’s actually a good way to learn good work habits. We do a lot to train new employees.

I operate three restaurants. It’s getting harder and harder to hire workers. People just don’t want to do this kind of work any more, but for young people it’s actually a good way to learn good work habits. We do a lot to train new employees.