In the November 28, 2017 Ask The Headhunter Newsletter, a reader interviews for a job at an acceptable salary, only to learn the employee benefits would mean a 20% reduction in compensation.

Question

Well, thanks for hitting me between the eyes… again. I’m talking about your recent column, More Money: What to ask for in a talent shortage. I was rationalizing a pursuit of a job offer.

It’s a great fit. I “did the job” with the Chief Information Officer and Director. The 30-minute phone interview turned into a 90-minute great discussion on where they want to be in 18 months. Now I have the technical interview.

It’s a great fit. I “did the job” with the Chief Information Officer and Director. The 30-minute phone interview turned into a 90-minute great discussion on where they want to be in 18 months. Now I have the technical interview.

The problem is that I misunderstood the benefits. Originally I thought it was a wash in salary, and that the cost of living, benefits, retirement, and bonus were going to be a 20% bump. With relocation to a warmer climate, it was a win-win. Then I got the benefits package.

I completely misunderstood. Once the benefits are factored in, it’s effectively about a 20% pay cut. There is no way I can absorb that. It’s a small shop and moving up would not be possible for a while given the staff they have in place.

(By the way, the recruiter for this company is absolutely amazing. She completely vetted me before she passed me to the company. She asked for my resume and then recommended that I change the wording on a couple of things. She never had me fill out an application. Then she set up the preliminary phone interview. We discussed salary but I think I heard what I wanted to hear. Fortunately, after that first interview, I asked for the benefits package. She sent it to me while I was on the phone with her.)

So here is my question for you. Do I go through with the technical phone interview and see if I can work with these folks? Then, before we put in any more time and money (and airfare), do I see if they can pay what I think I am worth? Or do I call it off now saying that it is a waste of our time if they are going to stick with their current salary range, given that the benefits are actually going to cost me money?

Nick’s Reply

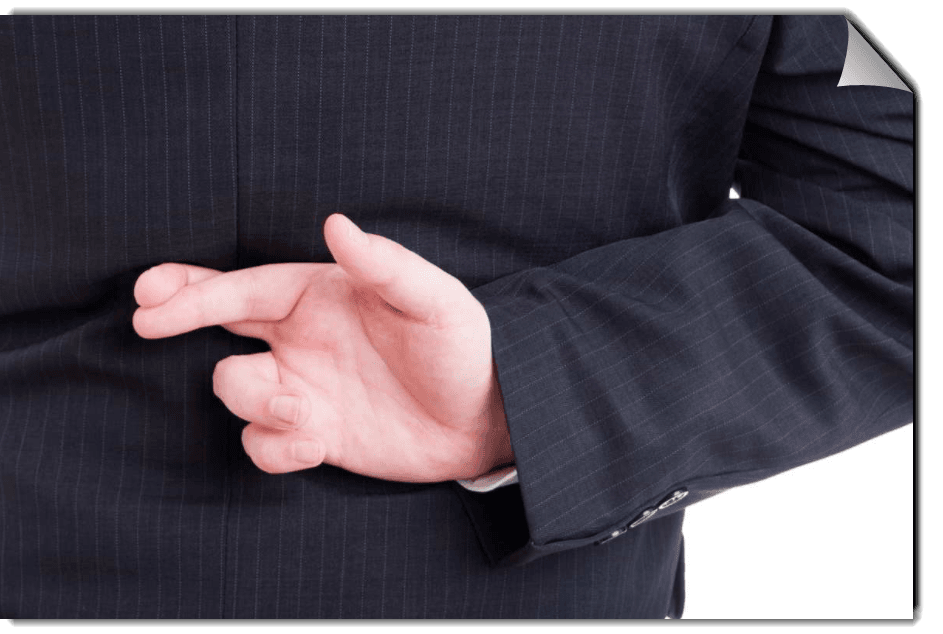

The recruiter tells you: “The salary range is $X-$Y and the benefits are industry-standard.” Once upon a time, that meant you could decide to go on the interview based on the salary range. Today, it’s a common trick to lead you into a series of job interviews that result in a job offer far lower than you expected — after you realize that a lousy benefits package has effectively lowered your total compensation.

It seems you learned an important lesson: Get the compensation facts before you dive into a time-consuming interview process. That means understanding all the bottom-line terms, including benefits — up front.

Benefits are compensation

Make no mistake: Benefits are part of compensation. Lame HR managers like to say, “Oh, our benefits package is industry-standard,” as if you should be impressed. Really? A company’s benefits package should be as competitive as the salaries it pays — that’s what gives a company an edge!

(Note to HR managers: Learn to use your company’s benefits as a tool to get the best candidates to accept your offers! That means you must construct great benefits packages. That’s a key part of your job.)

Benefits and bonuses are components of compensation. Until you can tally up the total, you don’t really know what the offer is — or whether the company is worth working for.

Post-Black Friday Pre-Holiday Early-Bird No-Questions-Asked SPECIAL!

The Complete Collection

(What’s in this 9-book collection? Click here to find out!)

Learn how to put the Ask The Headhunter methods to work in your job search — and SAVE!

TAKE 40% OFF the regular $49.95 price! ORDER NOW!

Use DISCOUNT CODE=TAKE40

This limited-time discount is ONLY for The Complete Collection! (Not for the individual books.)

Why are benefits a secret?

But don’t kick yourself too hard. Companies generally don’t hand out benefits details before interviews – though they should.

Many employers consider employee benefits a company secret that’s not disclosed until you show up for orientation. (Imagine a car dealer saying, “We’ll tell you what the warranty is, and how many wheels the car comes with, after you pay for the car.”) As you’ve learned, benefits are a critical part of any compensation package. Meager benefits can undermine a seemingly good salary.

So, ask about the benefits and the salary range before you invest time interviewing.

Look under the rug

When a company’s lousy benefits have such an adverse impact on a compensation deal, there’s probably something wrong with the company. There’s dirt under that fine-looking rug. So turn up a corner and look underneath.

Good employers offer good benefits. And they don’t hide such information. When they do, it’s the oldest sales trick in the book: They count on you to rationalize a bad deal because you’ve already put so much time and effort into it.

I don’t see any evidence that you misunderstood. If you didn’t have the benefits information in advance, how could you really judge whether this was a good opportunity or a waste of time? How could you have judged the whole compensation package?

The recruiter’s role

What’s “amazing” about the recruiter is that she did not disclose up front that the company’s benefits package is lousy.

I assure you, she knows, because other candidates have experienced the same shock you did. While I give her credit for some of the things she did (and didn’t do — like demanding an application), if she’s a really good recruiter, she reviews all compensation components before she recruits people like you. I’d never pitch a company with lousy benefits to

any potential candidates. I’d wind up wasting their time and mine. My guess is she’s lost other good candidates late in the process, after all the facts came out.

Ask to see the benefits

Job seekers rarely ask to see benefits, retirement, vacation, bonus and commission details before agreeing to interview. That’s a mistake. Employers don’t like sharing such information until they make an offer, but that’s disingenuous. Any company with great benefits is more than happy to use them to entice good candidates to interview.

One of my favorite HR ruses is this statement: “We offer the same benefits to all employees. We cannot change our benefits for just one person.” People hear that and they shrug. Of course they can’t change their benefits just for me. That would be unfair to all the other employees. Then an applicant rationalizes that there’s no choice. If I want this job, I have to settle for what everyone else gets. Wrong. If the employer really wants to hire you, it can improve other terms of the offer to compensate (remember that word?) for poor benefits. (We’ll get to that in a minute.)

Companies with lousy benefits hide them, and HR managers try to make job applicants feel it’s “unprofessional” to ask for the information in advance. What’s unprofessional is luring people into dead-end interviews.

Don’t kid yourself

I see it again and again. Job applicants get offended and angry about the details of a job offer at the end of a grueling interview process — because they failed to ask about all the terms before they invested all that time and trouble to interview. Of course the terms matter! Don’t kid yourself! Understand the fundamentals of the deal before you work so hard to get it.

Many career experts recommend proceeding with the hiring process anyway. “Hey, you have a shot at a job! Why blow it by bringing up money?” They will tell you to wait until the offer stage to convince an employer to do what it already told you it will not do. Don’t kid yourself. That kind of advice reveals the advisor doesn’t have an answer for your predicament, because the advisor believes in fairies and miracles.

It’s up to you, but I would not rationalize any more, or move further into this process, now that you know the benefits are a deal breaker. Talk to the recruiter. Tell her your concerns. Tell her you’re very surprised and dismayed at the benefits package.

How to Say It

“Thanks for sharing the company’s benefits package. Unfortunately, it’s not competitive and would represent an effective 20% pay cut. I’d love to continue our interviews, but first I need the company’s commitment to compensate me for the significant difference in benefits they are proposing. It would be a waste of our time to keep talking about the job if the compensation terms — and that includes benefits — aren’t acceptable. Will your client make that commitment?”

What to ask for next

Don’t be too hard on yourself. If the salary range was acceptable and you based your decision to have a preliminary phone interview on that, I think you took a reasonable risk to explore the job. While you should have asked to see all the benefits up front, 99% of applicants don’t ask until after a job offer is tendered. At least you asked early in the process.

What troubles me is that the recruiter didn’t disclose the problem with benefits when she first spoke with you. I put that on her. So I’d let the recruiter know what’s wrong immediately.

Don’t say no to proceeding. Instead, tell her what the terms need to be so they’re acceptable to you. Don’t worry about whether the employer is likely to accept your terms. The point is to establish what it will take before you are willing to proceed. The details are up to you. Here are some possible gimmes:

- Higher salary, commensurate with the loss of benefits value. I think this is the best offset because it will fund the difference.

- A starting bonus, but keep in mind this would be a one-time payment that does not affect future pay. I’m not a big fan of this, unless you can’t negotiate higher salary. Then you must decide whether it’s worth it.

- A higher bonus structure that effectively makes up for the loss in benefits. Just keep in mind that bonuses are not guaranteed. So ask for a guaranteed bonus.

- Other terms that might satisfactorily compensate you.

Clearly, they are impressed enough with you to go the next step. They want to pursue this with you. That gives you leverage. Don’t be afraid to use it wisely and appropriately. Hey — if they have no qualms about offering you poor benefits, don’t worry that you’re asking for too much! Let them say no, or let them fix the problem.

Manage the recruiter

It seems you’ve found a pretty good recruiter — she’s done a lot right. Take advantage of that.

I’d tell the recruiter that if this deal doesn’t work out, you’d like to work with her again, if she commits to vetting these deals more thoroughly for you in the future, before setting up even phone interviews. Like this employer, she has recognized a good candidate. She is likely to work harder for you in the future because you represent a really good chance for her to impress another client — and to earn a good fee!

Make the employer work for it

Don’t get tricked into dead-end interviews by an employer that uses crummy benefits to effectively lower a job offer.

An employer uses interviews to test a candidate, to determine whether it’s worth proceeding with the hiring process. Job candidates should do the same. Test the employer. Will its compensation package, including benefits, bonus and other terms, measure up to your requirements? Then determine whether to proceed. Make them work for it, just like you do in your interviews.

I’d love to know how this turns out. My comments and suggestions are obviously limited to what I know. You’re the one that must live with the choice you make – so please use your best judgment.

What information do you demand before you agree to interview? We’ve covered only a couple of things here — salary range and benefits. What surprises have you encountered only after you’ve invested a lot of time in an “opportunity?” What else should this reader assess before going any further?

: :

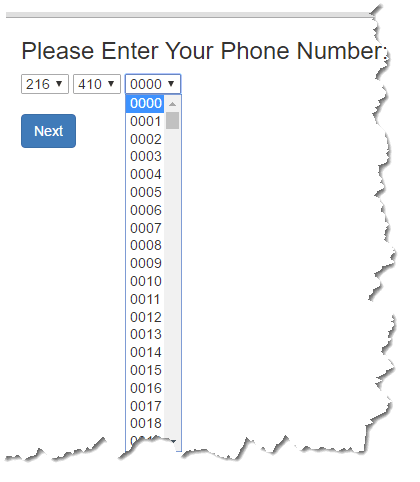

I’ve read many of your posts about job boards, including Job Boards: Take this challenge, but it was one about The Bogus-ness of Indeed.com that really got my attention because it has over 200 comments on it, and because now I’ve seen how Indeed works for employers — and I’m LMAO!

It’s a great fit. I

It’s a great fit. I  After three interviews that included a lengthy presentation on

After three interviews that included a lengthy presentation on  Earlier this week a recruiter contacted me. The salary was stated as a maximum only, and it would mean a 20% raise from my current salary. Even though I am not looking, I went ahead and applied.

Earlier this week a recruiter contacted me. The salary was stated as a maximum only, and it would mean a 20% raise from my current salary. Even though I am not looking, I went ahead and applied.

I dunno — maybe we should start Job Seekers Anonymous? It’s time we worked up a way to address employers who claim to want “exceptional talent” but expect you to turn off your talent and apply-for-jobs-by-numbers.

I dunno — maybe we should start Job Seekers Anonymous? It’s time we worked up a way to address employers who claim to want “exceptional talent” but expect you to turn off your talent and apply-for-jobs-by-numbers. “Hi, I’m Bill, a seasoned pro in [your field]. I’m interested in working for your company because it’s a shining light in our industry. But I’m puzzled by something. As a very busy [programmer, marketer, whatever] I don’t have time to waste with impersonal cattle-calls and online job forms, so I’m surprised your company is advertising rather than recruiting only the right people thoughtfully. I select potential employers very carefully. I’m ready to meet with your [marketing manager] to show how I can do the job to bring more profit to your bottom line.

“Hi, I’m Bill, a seasoned pro in [your field]. I’m interested in working for your company because it’s a shining light in our industry. But I’m puzzled by something. As a very busy [programmer, marketer, whatever] I don’t have time to waste with impersonal cattle-calls and online job forms, so I’m surprised your company is advertising rather than recruiting only the right people thoughtfully. I select potential employers very carefully. I’m ready to meet with your [marketing manager] to show how I can do the job to bring more profit to your bottom line.

I do not work in the tech field where I know these are common. I’ve worked in marketing for 15 years, won awards, and worked for some top-name businesses. But recently I have encountered many recruiters that want you to prove your worth.

I do not work in the tech field where I know these are common. I’ve worked in marketing for 15 years, won awards, and worked for some top-name businesses. But recently I have encountered many recruiters that want you to prove your worth.

Nick, I need your help. I’m in a very tough spot with salary negotiations. HR told me the salary range for the position ($65K-$70K) on the phone before our interviews. T

Nick, I need your help. I’m in a very tough spot with salary negotiations. HR told me the salary range for the position ($65K-$70K) on the phone before our interviews. T

A few years ago you called out employers for their misguided crying about the talent shortage. (

A few years ago you called out employers for their misguided crying about the talent shortage. ( A few years ago, one of the student workers at the library was selected (her name was randomly drawn) to keep the clothes and accessories the Student Success Center and a women’s organization purchased for her as part of a dress-for-success workshop. She also got to have her hair done, and learned how to do her makeup. She was so thrilled and grateful, because she couldn’t afford to go to Kohl’s and spend $350.00 on a few new (professional) outfits for herself.

A few years ago, one of the student workers at the library was selected (her name was randomly drawn) to keep the clothes and accessories the Student Success Center and a women’s organization purchased for her as part of a dress-for-success workshop. She also got to have her hair done, and learned how to do her makeup. She was so thrilled and grateful, because she couldn’t afford to go to Kohl’s and spend $350.00 on a few new (professional) outfits for herself.