In the February 19, 2013 Ask The Headhunter Newsletter, a job applicant resists lower job offers “justified” with salary surveys:

I don’t like telling employers my salary history when they ask, and I know you advise to keep the information private. But I’m happy to tell an employer what salary range I expect. That way we’re all on the same page, or why bother having interviews? The problem is that employers sometimes gasp when you tell them you want more than an average salary. When they trot out a salary survey and tell me what I’m asking is too far on the high end, how do I say, “You should offer me more money?”

Nick’s Reply

Here’s the advice I offer in my PDF book Keep Your Salary Under Wraps:

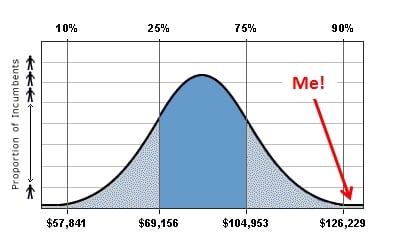

If an employer cites a salary survey, ask to see the curve. Point to the leading edge of the curve, where the most unusual individuals are earning the highest salaries.

How to Say It

How to Say It

“I believe I’m on the leading edge of the curve. If I can’t prove that to you during our interviews, then you shouldn’t hire me. But please understand that I’m not looking for a job on the middle of the graph, this part of the curve.” [Point to the fat middle of the graph, where average workers earn average salaries.]

Your challenge is to demonstrate that your performance would indeed be at the leading edge of the curve.

I realize this borders on sounding cocky, but remember that if you don’t make your case in this meeting, you probably won’t get another chance. Be polite and respectful, but be firm. Your future compensation is on the line. Obviously, you must be prepared to justify what you can do that makes you worth a higher salary. There is no way around this. Employers don’t increase job offers just because people ask for more money. You have to give them good reasons based on what you will bring to the job. (You also must decide what is the minimum you will accept. This article will help you flesh that out: How to decide how much you want.)

This is where I call employers and human resources departments to task. While the job offers they make are often only mediocre at best, they claim they reward “thinking out of the box,” and that they are in the forefront of their industry. This is where they need to prove it. I suggest you politely (and perhaps quizzically) address the person you’re negotiating with.

How to Say It

“I’ve studied your company carefully, and I’m impressed at your philosophy. Your company prides itself on thinking and acting out of the box. That’s why I’d like to work here. Of course, out of the box is another way of saying on the edge of the curve. I’d like to show you how I can bring edge of the curve performance to the job — but of course that means edge of the curve compensation. If you will outline what you consider to be exceptional performance, I’ll try to show you how I will deliver.”

There is nothing easy about this. You must do your homework in advance. (For more details on this assertive approach, please see The Basics.) It’s important to open a serious discussion on salary. Companies, and HR departments especially, love to talk about how people are their most important asset. We all know that assets are cultivated so they’ll grow. We want to maximize their value. So we hire the best people, pay them the most, and cultivate them well so they’ll pay off, right?

Well, that’s not what happens when an employer insists on knowing your past salary so it can base a job offer on it. It’s hypocritical — and risky business. It’s how companies lose great candidates who won’t stand for average job offers.

But you can make an employer’s pretensions work for you, if you can be firm but diplomatic, emphatic but gentle, challenging but cooperative. My suggestion above is one way to do it.

Putting Ask The Headhunter to work usually requires saying something to someone to make it pay off. My suggestions about How to Say It are not the only way. There are many good ways to tell an employer that you want more money when you’re negotiating a better deal.

What do you do when you want more money? How would you say it — and what’s worked for you?

: :