In the January 21, 2014 Ask The Headhunter Newsletter, Nick asks readers for help with an upcoming TV news interview:

There’s no question from a reader this week. Instead, I’m asking all of you readers a question. May I have your help?

I’ve been asked to appear on a TV news show to discuss how HR is using Big Data to watch you at work — and to process your job application without interviewing you. I’d like your input on the topic so I can frame my comments with your interests in mind. I’ll share a link to the program after it airs, and we can discuss it further then.

[UPDATE: Here’s the link that includes video from the TV program: Big HR Data: Why Internet Explorer users aren’t worth hiring]

Nick’s Question for You

Are you frustrated because employers reject your job application out of hand without even talking to you? Tired of online application forms kicking you out of consideration because you took too long to answer questions, or because you failed to disclose your salary history?

Are you frustrated because employers reject your job application out of hand without even talking to you? Tired of online application forms kicking you out of consideration because you took too long to answer questions, or because you failed to disclose your salary history?

Wait — America’s employment system is getting even more automated and algorithm-ized. According to a new report in The Atlantic, the vice president of recruiting at Xerox Services warns that:

“We’re getting to the point where some of our hiring managers don’t even want to interview anymore.” According to the article, “they just want to hire the people with the highest scores.”

The subtitle of that Atlantic column (They’re Watching You At Work by Don Peck) reads: “The emerging practice of ‘people analytics’ is already transforming how employers hire, fire, and promote.”

Does that worry you?

If all goes according to plan (hey, this is TV — all schedules are subject to change), Atlantic columnist Don Peck and I will talk about the rise of Big Data in the service of HR — and I want your input in advance, because I’m worried about the conclusions Peck draws in his article. It’s a very long one (8,600+ words), but it illuminates some of the technology that’s frustrating your job search. Please have a look at it, and post your suggestions to help me frame my comments for this TV program.

Here are the Big Problems I see with this Big Data approach to assessing people for jobs and on the job:

The metrics are indirect.

The vendors behind these “tools” don’t directly assess whether a person can do a job. Instead, they look at other things — indirect assessments of a person’s fit to a job. For example, they have you play a game and they measure your response times. From this, they try to predict success on the job. That determines whether you get interviewed.

The problem is that we’ve known for decades that this approach doesn’t work. Wharton researcher Peter Cappelli throws cold water on indirect assessments:

“Nothing in the science of prediction and selection beats observing actual performance in an equivalent role.”

All that’s being thrown into the mix by these “assessment” vendors is Big Data. But more data doesn’t change anything. In fact, it makes things worse if the data are not valid predictors of success. It’s worse because indirect assessment leads to false negatives (employers reject potentially good candidates) and to false positives (they hire the wrong people for the wrong reasons).

The conclusions are based on correlations.

These tools predict success based on whether certain characteristics of a person are similar to characteristics of a target sample of people. For example, Peck’s article says that “one solid predictor of strong coding [programming] is an affinity for a particular Japanese manga site.” (Manga are Japanese comics.)

Gild, the company behind this claim, says it’s just one correlation of many. But Gild admits there’s “no causal relationship” between all the Big Data it gathers about you and how you perform on the job.

In what can only be called a scientific non sequitur, Gild’s “chief scientist” says “the correlation, even if inexplicable, is quite clear.”

The problem: A basic tenet of empirical research is that a correlation does not imply causality, or even an explanation of anything. Data tell us that people die in hospitals, and that correlates highly with the presence of doctors in hospitals. All jokes aside, that correlation doesn’t mean doctors kill people. Except, perhaps, in the world of Big HR Data: If you’re selling “people analytics,” then playing a game a certain way means you’ll work a certain way.

When we pile specious correlations on top of indirect assessments (What animal would you be if you could be any animal?), we wind up with no good reasons to make hiring decisions, and with no basis for judgments of employees.

INTERMISSION: There’s a hidden lesson for recruiters in Big Data.

Hanging out at a manga site doesn’t improve anyone’s ability to write good code — nor does it predict their success at work. But, it might mean that a recruiter can find some good coders on that manga site — the one reasonable conclusion and recruiting tactic that none of the people Peck interviewed seem to have thought of!

I don’t think Peck wrote this article to promote “people analytics” as the solution to the challenges that American companies face when hiring, but he does seem to think the Kool-Aid tastes pretty good. I think Peck over-reaches when he confuses useful data that employers collect about employee behavior to improve that behavior, with predictions based on silly Big Data assumptions.

To entice you to read the article and post your comments, I’ll share a couple of highlights in the article that kinda blinded me. Well, the assumptions behind them were blinding, anyway:

Spying tells us a lot.

In further support of indirect assessments of employees and job applicants, Peck cites the work of MIT researcher Sandy Pentland, who’s been putting electronic badges on employees to gather data about their daily interactions. In other words, Pentland follows them around electronically to see what they do.

“The badges capture all sorts of information about formal and informal conversations: their length; the tone of voice and gestures of the people involved; how much those people talk, listen, and interrupt; the degree to which they demonstrate empathy and extroversion; and more. Each badge generates about 100 data points a minute.”

Peck notes that these badges are not in routine use at any company.

It’s just a game.

A lot of the “breakthroughs” Peck writes about come from start-up test vendors like an outfit called Knack, which creates games “to suss out human potential.” Knack continues to seek venture funding, and the only Knack client mentioned in the article is Palo Alto High School, which is using Knack games to help students think about careers.

“Play one of [Knack’s games] for just 20 minutes, says Guy Halfteck, Knack’s founder, and you’ll generate several megabytes of data, exponentially more than what’s collected by the SAT or a personality test.”

The big d ata gathered, writes Peck,

ata gathered, writes Peck,

“are used to analyze your creativity, your persistence, your capacity to learn quickly from mistakes, your ability to prioritize, and even your social intelligence and personality. The end result, Halfteck says, is a high-resolution portrait of your psyche and intellect, and an assessment of your potential as a leader or an innovator.”

Let’s draw a comparison in the world of medicine; it’s an easy and apt one: If more megabytes of game data can be used to generate more correlations, could doctors diagnose patients more effectively by collecting bigger urine samples? Because that’s the logic.

No sale.

I don’t buy it. I want to know, can you do the job?

Some Big Data about employee behavior can be analyzed to good effect. For example, Peck reports that Microsoft employees with mentors are less likely to leave their jobs, so Microsoft gets mentors for them. But he seems to easily confuse legitimate metrics with goofy games of correlation. And the start-up companies he profiles don’t seem to be on any leading edge — they’re mostly trying to sell the idea that Big Data in the service of questionable correlations makes those correlations worth money.

(To learn the ins and outs of legitimate employment testing, see Erica Klein’s excellent book, Employment Tests: Get The Edge.)

Big Deal.

We know that what Peter Cappelli says about the science of prediction is correct. But I think Arnold Glass, a leading researcher in cognitive psychology at Rutgers University, says it best:

“It has been known since Alfred Binet and Victor Henri constructed the original IQ test in 1905 that the best predictor of job (or academic) performance is a test composed of the tasks that will be performed on the job. Therefore, the idea that collecting tons of extraneous facts about a person (Big Data!) and including them in some monster regression equation will improve its predictive value is laughable.”

It seems to me that HR should be putting its money into teaching HR workers and hiring managers to hang out where the people they want to hire hang out, and into teaching them how to get to know these people — and how good they are at their work.

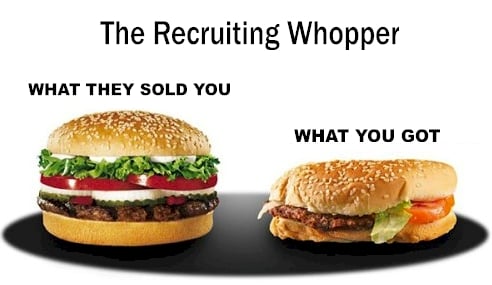

In the meantime, is it any surprise to any job seeker today that employers mostly suck at recruiting the right people and at conducting effective interviews?

If you have questions or thoughts you’d like me to raise in this forthcoming TV program, please post them. I’ll try to use the best of the bunch. I wish I could tell you that hanging out on my blog causes employers to hire you. Thanks!

[UPDATE: Here’s the link that includes video from the TV program: Big HR Data: Why Internet Explorer users aren’t worth hiring]

: :

While Scott Cook, Intuit’s founder, was serving on eBay’s board, he complained that eBay needed to stop recruiting from Intuit. The DOJ suit contends that Cook and former eBay CEO Meg Whitman agreed not to hire one another’s employees.

While Scott Cook, Intuit’s founder, was serving on eBay’s board, he complained that eBay needed to stop recruiting from Intuit. The DOJ suit contends that Cook and former eBay CEO Meg Whitman agreed not to hire one another’s employees.