In the April 14, 2020 Ask The Headhunter Newsletter a reader questions the wisdom of working for staffing firms.

Question

I had a contract job with a staffing firm that officially ended a couple of months back. The firm said that they were still looking for other clients to send me to, but just now told me that I’m released.

Do you think it’s even (or ever) worthwhile to get involved with staffing firms like this to look for jobs? I’m also asking because, since a lot of them have “presented” me to their potential clients, my reputation may have been “poisoned” from that. They may have been (probably actually were) “dialing for dollars,” and I never hear anything back from them.

I respect your take on things and I’d like to hear what you think, and what other folks on the discussions think, too.

Nick’s Reply

Staffing firms can be a dicey proposition. You’ve no doubt noticed a trend in the past decade. Companies seem eager to off-load (“outsource”) hiring to “staffing firms” that recruit and hire workers, then rent them to real employers. I have strong opinions about the effects of the staffing industry — also known loosely as the consulting industry — on the overall economy, and I make no bones about it: Consulting: Welcome to the cluster-f*ck economy. But my opinions should not stop you from exploring ways to profit from getting a gig through a good staffing firm — so let’s discuss this.

Why staffing firms?

It seems the key motivation for companies to use rented, or “contract,” or temporary workers is to eliminate certain overhead costs of actually hiring employees directly. The staffing firm handles recruiting, payroll, benefits and HR functions, among other things. When the worker is technically on the payroll of a staffing firm, the employer also avoids certain risks and costs of firing people, because the employer isn’t “firing” anyone. It is merely “sending them back” to the staffing firm.

In my opinion, the biggest risk to companies that use staffing firms is that they relinquish their most important competitive edge — expertise in finding and hiring the very best workers.

The problem with staffing firms

There are so many shady, boiler-room “staffing” operations that the few good ones suffer from the overall poor reputation of the business. The odds are high that any staffing firm that solicits you is indeed dialing for dollars, or to use a more technical term, “throwing spaghetti against the wall.” They are simply not good at matching workers to jobs and companies.

The worst operate massive overseas call centers and are clueless about the work you do. Along with scads of random resumes, they’ll throw the kitchen sink at a client and let it pick the candidates. If someone the client chooses isn’t working out, the worker is quickly replaced. This “churn” practice is supposed to substitute for careful, appropriate placements.

And you’re right, an unscrupulous staffing firm that scraped your resume from the Internet probably distributed it without your knowledge — possibly indiscriminately. That makes you look bad.

Can staffing firms hurt you?

As you suspect, an HR department that receives your resume for the wrong job could tag your record in its database with a big fat X. That could make it harder for you to get in the door later. That’s one reason to work only with reputable staffing firms you trust — not just those that solicit you.

Should you worry about this? You really can’t do much about it. When you post your resume online, it’s fair game. Anyone can forward it to any data dumpster anywhere. But don’t fret. Even if your reputation is thereby “poisoned” at some companies, all it really takes is one very good reference or personal referral to fix that. (This is precisely why personal contacts are so important. Please see Skip The Resume: Triangulate to get in the door.)

I think the worst thing a staffing firm could do to you is put you into a series of wrong short-term assignments over a lengthy period of time. This makes a mess of your work history. Good luck explaining your resume to a real employer.

How should I vet staffing firms?

There are good staffing firms out there. They might be very big and they might be very small and specialized. If this is how you prefer to work — as a consultant — it’s up to you to perform due diligence to identify them. A friend of mine in the staffing business shared some excellent advice many years ago. These 4 tips are still valid today.

- Always check references. When you’re deciding on a staffing firm, try to work with people you know and trust who are reputable. They can help you through this whole process. If you have to go to someone you don’t know, check their references. And don’t just use references they’ve given you; use your own contacts.

- Talk to your peers. As a potential employee, it may seem weird to ask a company for references, but it’s very important. If I were considering a job with a consulting firm, I’d like to talk to other employees, especially employees who are in a similar role to what I’d have.

- Understand the contract. Make sure you read your agreement with the staffing firm (and any subsequent agreement you must sign with the company you get assigned to) carefully and make sure everything you agreed to verbally is documented and signed. It doesn’t matter what the consulting firm is telling you if the contract says something else. Contracts vary all over the board. Make sure you know what you’re signing up for. (Please don’t miss: Bait & Switch: Games staffing firms play.)

- Expect the unexpected. Even the best consultants (that’s usually how the staffing firm will refer to you) will encounter problems. Take for example the consultant who didn’t get paid for two months by the staffing firm they’d been with for 20 years. The firm suddenly changed management, and lost its ethics. That kind of horror story can happen to the most experienced consultants. That’s why it’s so important not to become complacent.

How can I find the best staffing firms?

If you want to work through staffing firms, invest a little time to find the best ones. Here are 6 steps to follow.

- Select employers. Make a list of the 5 best companies in your line of work, in the geographical areas where you want to live — the actual employers where you would be working every day.

- Make a call yourself. Call the HR VP or, better, the head of the department you want to work in.

- Introduce yourself. Explain very briefly what kind of work you do; maybe just mention your job title. (Do not turn this into a pitch for a job.)

- Get a referral. Then ask, “May I ask you what is the best staffing firm in [IT, for example] that you use for your company’s contract hiring?”

- Select, don’t settle. Don’t settle for staffing firms that solicit you out of the blue. Pursue the ones whose clients love them. If the person you speak with names their preferred firm, ask for the name of the representative that handles their account. Thank them and end the call. Now you have (a) identified a reputable staffing firm, (b) you know they work with a company you might like to work for, (c) you have a name to drop (the manager you just spoke with), and (d) you know whom to call next.

- Take the initiative. Call the rep at the staffing firm. Introduce yourself very briefly, say that “Your client, So-And-So, recommended that I call you. They said your firm is one of the best in the [IT] field. I’m looking for a new position. Would you like to talk?” When the rep hears that their client sent you, the rep hears dollar signs.

Not everyone you call will tell you which staffing firm they use, but this approach is probably usual and disarming enough that some will. Likewise, not every staffing firm you then contact will help you. But this approach beats fielding calls from fast-talking recruiters at questionable staffing firms you know nothing about. So keep at it.

While I’d advise you to pursue full-time, direct jobs first, I would not tell you to rule out staffing firms. Many employers rely on them heavily. Just know what you’re getting into. In any case, when you make those calls to HR or to department heads, you might end by asking, “By the way, do you also hire direct?”

Get ready

This is hardly an exhaustive discussion about staffing firms and how to deal with them effectively. I expect other readers will share very useful information and raise issues I haven’t even touched upon. But get ready. This is an important topic because the employment world is about to change again dramatically.

The coronavirus crisis has eliminated a lot of jobs — that’s plenty of drama. But as the downturn subsides, the healthiest companies will be desperate to re-fill many of those jobs. It will be a time of opportunity — but also opportunism. Many unscrupulous staffing firms will suddenly appear, trying to capitalize on the new drama. You’ll get a lot of calls. I expect a lot of “churn” as people who are understandably desperate for jobs take positions they should not accept.

Before the lousy staffing firms contact you, find the best ones and contact them.

What’s your experience with staffing firms? What advice would you give this reader?

: :

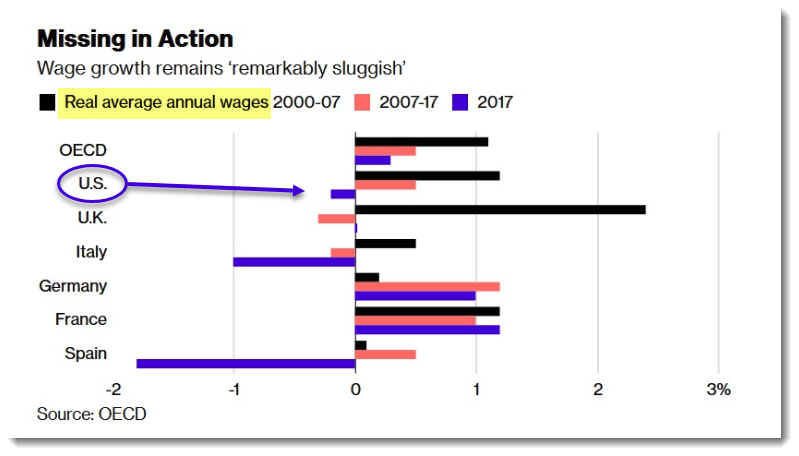

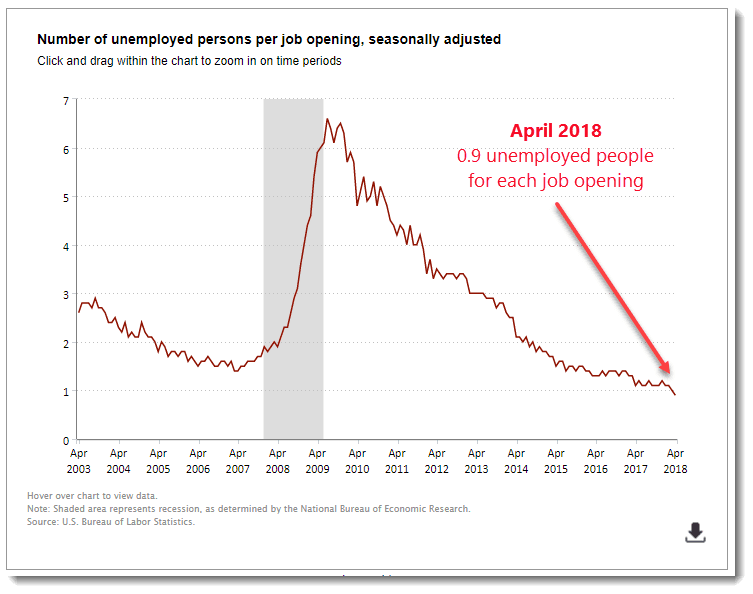

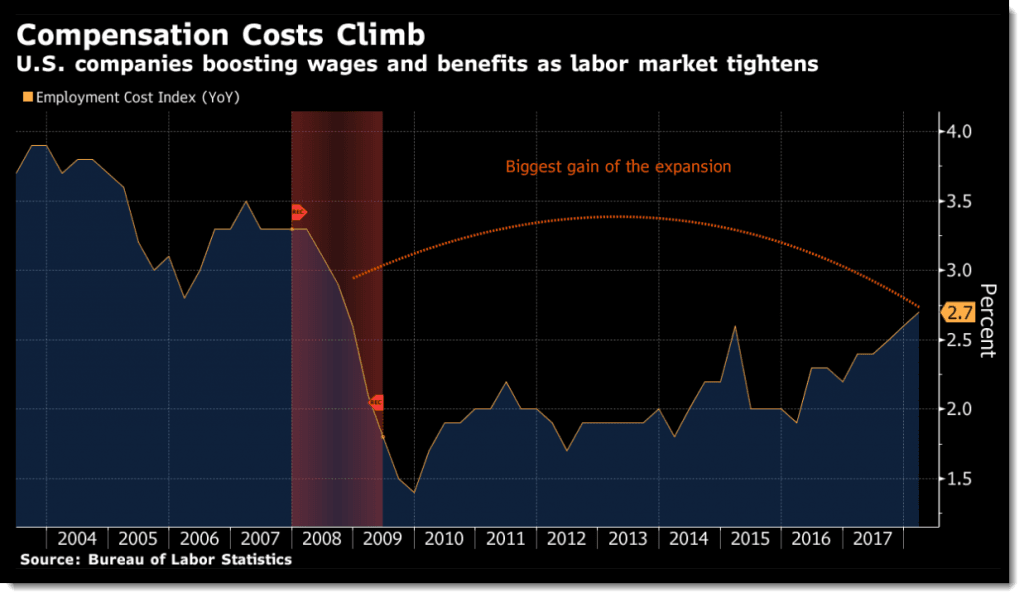

Every month the Department of Labor issues the “jobs numbers” and the “unemployment numbers” and everyone goes gaga about how great things are. There are loads of jobs to apply for! There’s a shortage of talent, so that’s good tidings for us job seekers! You’d think simple market economics would mean higher salaries and job offers.

Every month the Department of Labor issues the “jobs numbers” and the “unemployment numbers” and everyone goes gaga about how great things are. There are loads of jobs to apply for! There’s a shortage of talent, so that’s good tidings for us job seekers! You’d think simple market economics would mean higher salaries and job offers.

You’ve probably already read this on Slate. Three economists conducted a study that asks,

You’ve probably already read this on Slate. Three economists conducted a study that asks,  I’m an avid follower and have found Ask The Headhunter positively inspirational. I especially enjoy pushing back on senior executives for their lame hiring practices and nonsensical

I’m an avid follower and have found Ask The Headhunter positively inspirational. I especially enjoy pushing back on senior executives for their lame hiring practices and nonsensical  Today I received an e-mail from the Screening Company, asking for W-2s from the employer I worked for between 2005-2011. I happen to know that companies verify prior employment electronically, so I asked the Consulting Firm why they needed W-2’s. He said the Screening Company couldn’t confirm my employment. This made no sense to me. I said I would call the Screening Company to work this out, since there was a number on the e-mail for customer service. The recruiter at the Consulting Firm said not to do that, and that I should download the W-2s from the IRS.

Today I received an e-mail from the Screening Company, asking for W-2s from the employer I worked for between 2005-2011. I happen to know that companies verify prior employment electronically, so I asked the Consulting Firm why they needed W-2’s. He said the Screening Company couldn’t confirm my employment. This made no sense to me. I said I would call the Screening Company to work this out, since there was a number on the e-mail for customer service. The recruiter at the Consulting Firm said not to do that, and that I should download the W-2s from the IRS. I don’t see how your prior W-2 (salary) information is anyone’s business. If the Consulting Firm does its job right, it knows you’re qualified to do the job its client needs you to do. Otherwise, what’s it charging its clients for? What does it matter where you worked in 2011 or what you were paid? Just sayin’.

I don’t see how your prior W-2 (salary) information is anyone’s business. If the Consulting Firm does its job right, it knows you’re qualified to do the job its client needs you to do. Otherwise, what’s it charging its clients for? What does it matter where you worked in 2011 or what you were paid? Just sayin’. I have no idea how any of these entities can even stay in business with so many hands in the till. You’re not hired to work; you’re rented out to do work. The price being charged for your work far exceeds what you’ll see in your paycheck. Everyone’s getting paid for your work; everyone’s getting a taste of your pay. Good luck figuring it out, because I wouldn’t even start trying to. All I see is a hole in the economy, where money goes without the creation of any value. (See

I have no idea how any of these entities can even stay in business with so many hands in the till. You’re not hired to work; you’re rented out to do work. The price being charged for your work far exceeds what you’ll see in your paycheck. Everyone’s getting paid for your work; everyone’s getting a taste of your pay. Good luck figuring it out, because I wouldn’t even start trying to. All I see is a hole in the economy, where money goes without the creation of any value. (See  My advice is, work for your employer. Avoid any drain of economic value from your work. Don’t let middle-men interfere with the employer-employee relationship. The risk you take when you participate in this kind of cluster-f*ck economy is that you are not the worker. You are the product. You become an interchangeable part. Worse, you become a returnable interchangeable part.

My advice is, work for your employer. Avoid any drain of economic value from your work. Don’t let middle-men interfere with the employer-employee relationship. The risk you take when you participate in this kind of cluster-f*ck economy is that you are not the worker. You are the product. You become an interchangeable part. Worse, you become a returnable interchangeable part. My old consulting firm offered me the chance to interview for a full-time position in a smaller city over three hours away from where I am right now. My last contract ended a month ago, and just today I started a part-time job to slow the bleeding from my savings account.

My old consulting firm offered me the chance to interview for a full-time position in a smaller city over three hours away from where I am right now. My last contract ended a month ago, and just today I started a part-time job to slow the bleeding from my savings account. Now that you’ve already said no, you can stir the pot. I love stirring pots. We never know what the result will be, nor does it really matter. What matters is stirring the pot, because that makes both the scum and the good stuff rise to the top so everyone can see what’s really in there. The fun starts if someone skims off the scum and it splatters. A mess like that usually triggers change. No mess, no change.

Now that you’ve already said no, you can stir the pot. I love stirring pots. We never know what the result will be, nor does it really matter. What matters is stirring the pot, because that makes both the scum and the good stuff rise to the top so everyone can see what’s really in there. The fun starts if someone skims off the scum and it splatters. A mess like that usually triggers change. No mess, no change.