A reader faces a crisis of self-confidence when considering a higher-level job in the August 4, 2020 Ask The Headhunter Newsletter.

Question

How can a programmer know that they’re good enough to work as a developer? I found this interesting perspective posted on Quora from someone who has worked in software a long time: “If I only applied for jobs I was qualified for, I’d still be living with my parents.” The person said some companies will take a chance on you. Do you find this to be true?

Nick’s Reply

First, let’s clarify something for readers who don’t know a lot about computer software jobs. In simple terms, a programmer writes the code for a software project. A software developer can code, but is involved in almost all aspects of the project, including creating the concept for a product, designing it, and following it through to production. (Of course, not every programmer wants to become a developer!)

But what we’re going to discuss applies to almost any kind of job, and it applies to your desire to do more so you can earn more.

A chance at a higher-level job

I like that quote: “If I only applied for jobs I was qualified for, I’d still be living with my parents.”

Put another way, loads of employers may reject you because you haven’t already done the job they want to fill. They want to hire someone who’s been doing the job for the last five years — for less money. But you need just one employer to give you a chance to do something new and more advanced for higher pay. So you have to reach!

There are employers that will hire you because they need help and because they believe you will be able to rise to the demands of a higher-level job than you’ve ever had.

I find this to be true in almost all areas of work, not just programming and software development. Some of the best, most highly experienced professionals I know earned their chops by talking their way into jobs they had never done before. They learned through self-study, by taking necessary courses, by doing and by learning from others. I refer to them as people who can ride a fast learning curve without falling off. Companies hire them not just because of what they can do, but for what they can learn to do.

A programmer is good enough to work as a developer if they can show they are good enough, and if the employer allows for a learning curve (and perhaps also provides mentoring or training). For the employer to take a chance putting you in a higher-level job, you must take a chance and try to justify it.

Find an employer that values learning

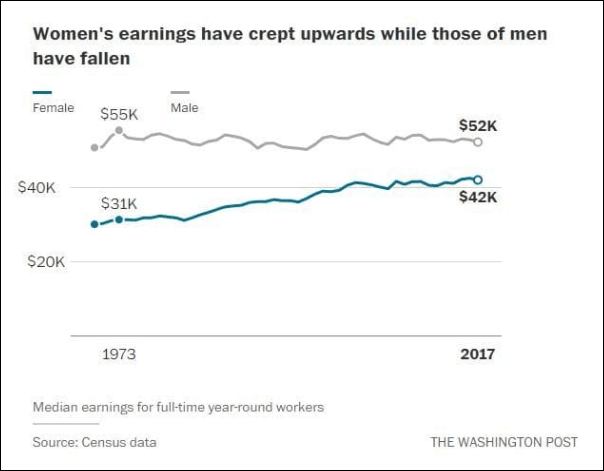

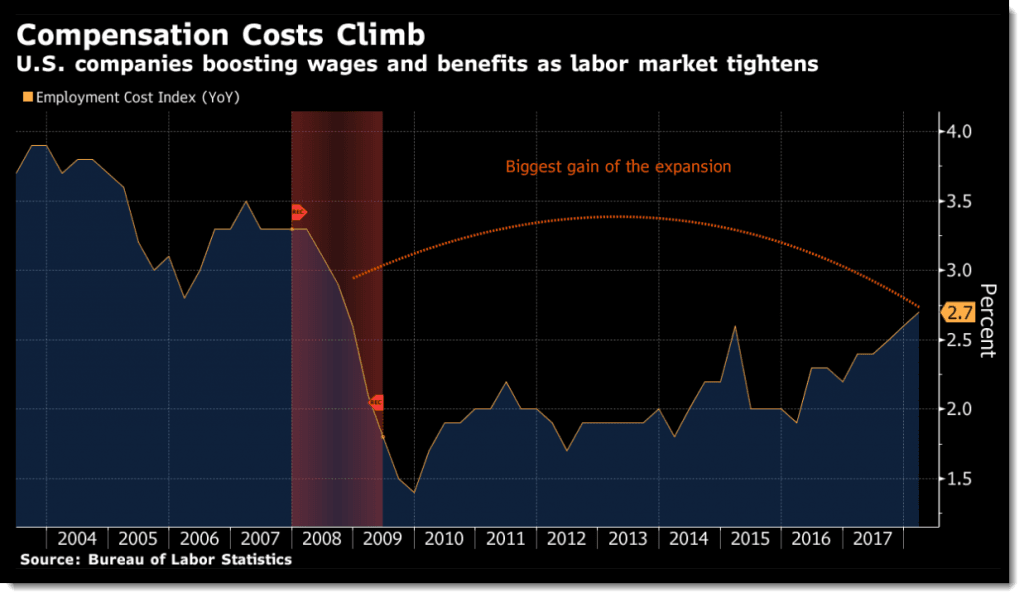

Peter Cappelli, a labor researcher I know at the Wharton School, has studied why people can’t get hired. He found that one big reason — obviously — is lack of skills. But he also found that there’s a shortage of specific skills because many employers don’t offer existing employees the training required to do more sophisticated work. They’d rather hire someone new who doesn’t need training.

Cappelli found that over the past 40 years employers drastically reduced their investment in training and development. I think this is partly the reason people started “job hopping.” They want to do new things. Programmers want to be developers. Customer service workers want to be be sales people. Bookkeepers want to be cost accountants.Some of these people make a leap by finding employers who welcome them. Moving up in your chosen career requires learning, even when employers don’t value training. So you may need to get your own training.

Help an employer take a chance on you

You cannot wait for an employer to judge whether you’re “good enough” to do a more sophisticated job. Figure it out yourself first, then help the employer take a chance on you. You may invest in appropriate training, or you may study and practice on your own. Then prepare a mini-business plan showing how you will do the job you want.

Your plan might include some guesswork because you can never know all you need to write up this kind of plan. But what impresses a good manager is how you defend and support your plan. If you can explain this clearly and simply, a good manager may decide you are a good investment and may be more likely to take a chance on you. (See The New Interview.)

It’s up to you to make a commitment, then don’t let your new boss down. Do what’s necessary to come up to speed quickly and prove you’re smart, dedicated, capable and dependable. I know managers who would jump over 10 complacent software developers to hire an enthusiastic programmer who shows evidence of self-motivation and an ability to learn fast.

You may have to hear a lot of No’s before you get to one Yes. But you need only one Yes.

Please don’t misunderstand. I’m not suggesting that any programmer can start managing a software development project, or that any bookkeeper can get hired as a cost accountant. But if you apply only for jobs you are qualified for today, you’ll never get the chance to demonstrate that you can ride a fast learning curve to the next step in your career.

How do you know you’re good enough? When you can convince that manager.

Do you ever apply for jobs that you’re probably not qualified for? Tell us how you pulled it off! Is it better to wait for a promotion than to change employers to move up? Is this a chicken-or-egg problem, since employers want to hire without offering any training?

: :

Can we charge new hires a penalty when they quit and leave us short-staffed? Can an employer state in an employment contract that if the new hire does not stay for a certain number of days, we retain the right to withhold $X to reimburse us for the time we spent training them? This Generation X and their job-hopping is costing this hospital tens of thousands and we are trying to find ways to teach them – work or lose money. Use us – lose money. We’re having a tough time with it. I did research. You came up.

Can we charge new hires a penalty when they quit and leave us short-staffed? Can an employer state in an employment contract that if the new hire does not stay for a certain number of days, we retain the right to withhold $X to reimburse us for the time we spent training them? This Generation X and their job-hopping is costing this hospital tens of thousands and we are trying to find ways to teach them – work or lose money. Use us – lose money. We’re having a tough time with it. I did research. You came up. Nick’s Question

Nick’s Question

This is the last Ask The Headhunter column for 2018. I’m taking a couple of weeks off for the holidays! See you next on January 8, 2019! Here’s wishing you a

This is the last Ask The Headhunter column for 2018. I’m taking a couple of weeks off for the holidays! See you next on January 8, 2019! Here’s wishing you a  I have a background in sales and marketing with high-profile accounts. I recently became certified in Lean Manufacturing to complement my

I have a background in sales and marketing with high-profile accounts. I recently became certified in Lean Manufacturing to complement my