Question

You don’t have to look far to find complaints about the job boards, including LinkedIn, Indeed, ZipRecruiter and the rest. I’ve seen some ridiculous claims about how many jobs these websites actually fill, but nothing scientific. Has the government tried to rein these guys in? Has there been any attempt to regulate the job boards?

Nick’s Reply

A quick search for “job board success rates” turns up nothing those boards can be proud of. At best, you’ll find loads of criticism about job boards. Several years ago, for a column I was writing for PBS NewsHour, I interviewed CareerBuilder. A spokesperson claimed the job board filled almost half of all jobs in the U.S. but no, she could not show me any data. Around the same time Indeed claimed 65% of hires. I’m still laughing.

A quick search for “job board success rates” turns up nothing those boards can be proud of. At best, you’ll find loads of criticism about job boards. Several years ago, for a column I was writing for PBS NewsHour, I interviewed CareerBuilder. A spokesperson claimed the job board filled almost half of all jobs in the U.S. but no, she could not show me any data. Around the same time Indeed claimed 65% of hires. I’m still laughing.

What are job boards good for?

One of the more pointed critiques is from employment software vendor CareerPlug. Based on pre-COVID 2019 data, this study slams the failure of job boards as the weakest source of hires:

“An applicant who applied directly from a company careers page was 23 times more likely to be hired than an applicant from a job board.”

“An applicant who applied from a referral was 85 times more likely to be hired than an applicant from a job board.”

When I hear that boards are helpful, it seems to be mainly freelancers and contractors (that don’t want permanent jobs) that defend them.

What are job boards good at? Producing job applications — up to 88% of them. The “job boards produce quantity,” reports CareerPlug, “but not always quality.” Virtually every study I’ve encountered concludes other sources of hires are dramatically more productive. More applications don’t yield more hires. The job boards are simply delivering more wrong candidates and more wrong job “matches.”

So, why do the job boards dominate the employment system and suck up the bulk of recruiting dollars? I think it’s simply because they are not regulated.

Time to regulate the job boards?

It’s long past time the federal government properly investigated this database industry — because it’s not a recruiting industry. It’s an amalgam of database jockeys and marketers producing and hawking software that fails epically at recruiting because it does little more than keyword matching. No job board I’ve encountered seems to understand the rudiments of recruiting.

What should be regulated? I’d settle, to start, for basic disclosures.

Require from all job boards:

- Outcomes Analysis: Show us the success rates for job hunters and employers that use a job board.

- Substantiate the marketing claims: Show us an audit trail for a job or resume posting.

- Disclose the source of each job posting (employer, recruiter, another job board?).

- Verify and certify that a job posting is real, and take down ones that are filled or canceled.

- Publish the original job post date and fill date.

- Disclose on each posting how many people have applied to date.

- Publish flowcharts of processes behind every job board.

- Disclose algorithms a board uses to make matches and rejections.

- Disclose salaries for all posted jobs. (This is already required by law in some states.)

That’s just a start.

Where is job board regulation?

To answer your question, I don’t believe government agencies have ever really attempted to regulate the job boards. Oh, there are anti-discrimination laws, truth-in-advertising laws, and more recently salary disclosure laws, but there is scant oversight and regulation of the recruitment advertising business. The Federal Trade Commission has prosecuted some recruitment scammers, but enforcement is too little and too rare. Chasing one-off scams does nothing to address the major players that dominate how you look for jobs and how employers try to hire.

I’m not a fan of regulation for its own sake, but an important purpose of government is to protect consumers from misinformation and systemic deceit in business. Interview 100 job seekers about their experiences with job boards and you’ll find plenty of deceit to justify a federal investigation — and regulation.

Do you think job boards should be regulated? What disclosures do you want to see? What regulations do you believe are necessary? What misrepresentations and deceits have you encountered? Is there a way to regulate job boards into being truly effective?

: :

Employers complain they can’t find the right people to hire and I think it’s because their recruiting is a herding task. They solicit too widely. This yields a preponderance of undistinguished candidates with a low probability of finding anyone that stands out.

Employers complain they can’t find the right people to hire and I think it’s because their recruiting is a herding task. They solicit too widely. This yields a preponderance of undistinguished candidates with a low probability of finding anyone that stands out.

There used to be a book titled something like 2,800 Interview Questions & Answers. Even today, you can find books that will automate your job interviews with canned repartee. These books feature 701 interview questions (and “best answers), or 201, or 189, 101 — or, How many interview questions you got???

There used to be a book titled something like 2,800 Interview Questions & Answers. Even today, you can find books that will automate your job interviews with canned repartee. These books feature 701 interview questions (and “best answers), or 201, or 189, 101 — or, How many interview questions you got???

20 HR recruiters from one [big-name defense contractor] contacted me via LinkedIn during 2019. One of them contacted me twice in two weeks, with the exact same message: Send me your most recent resume. She clearly didn’t know she had contacted me already. Others used the same message. I never heard from 19 of them again.

20 HR recruiters from one [big-name defense contractor] contacted me via LinkedIn during 2019. One of them contacted me twice in two weeks, with the exact same message: Send me your most recent resume. She clearly didn’t know she had contacted me already. Others used the same message. I never heard from 19 of them again.

In your previous postings, you suggest that LinkedIn is a poor medium for applying to companies. (See

In your previous postings, you suggest that LinkedIn is a poor medium for applying to companies. (See

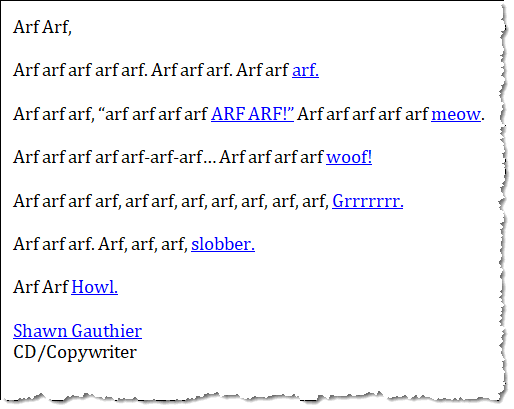

My friends and I are successful IT (information technology) types and receive calls about positions from headhunters often. We are all experiencing the following:

My friends and I are successful IT (information technology) types and receive calls about positions from headhunters often. We are all experiencing the following: Question

Question

Question

Question