In the August 30, 2016 Ask The Headhunter Newsletter, a reader cautions you to think twice before sending your information to “headhunters” you don’t know. They’re likely scammers.

Question

I recently had an experience with a headhunter(?) I do not know who sent me an unsolicited pitch to look at a job listing in my field in my city. The pitch was sent via LinkedIn with an attachment. I do not open attachments from people I do not know. This brings up the issue of cyber security in dealing with any kind of pitch about a job.

To confirm who I was dealing with, I called the main office of the headhunter’s firm. I got an answering service. Then I called the number the headhunter posted on LinkedIn, but got a vanilla message which did not identify the headhunter or the firm.

A reputable headhunter:

- will have a voicemail message that clearly identifies the office and the person.

- will not send an unsolicited attachment via LinkedIn.

Social media has been used successfully by hackers and scammers to mimic real identities to get unsuspecting people to open attachments that contain malware. For high-tech firms, like the one I work at, these kinds of threats are well understood.However, with the rise of ransom-ware and other forms of hacking for profit (e.g., stealing bank and credit card account information) the use of social media for social engineering is a real threat.

I suggest you post some advice for your readers about cyber security and how to avoid being taken in by scammers.

By the way: LinkedIn is a good vector for this type of social engineering attack because many people access it from work. If they open a malware-infested attachment, it could compromise a work computer along with its intellectual property secrets. So far, there has been no response to my voice mail replies to the headhunter, and I never touched the file attachment on LinkedIn.

Some headhunters who send unsolicited attachments might just be clueless. On the other hand, my experience is most recruiters send the job description after they’ve qualified the prospect as being interested, available, and a possible match for the job, not before. Do you agree?

Nick’s Reply

I agree, and you just wrote the warning you’ve asked me to give about e-mails soliciting you for anything. It’s all the more important when a scammer is connecting via LinkedIn to imply credibility.

Most likely, that’s not a headhunter at all, but a phishing expedition. It’s how scammers obtain personal information they can use to steal your identity. We can’t blame headhunters for something like this, because such scams routinely mimic anything that might lead a sucker to open an e-mail and an attachment.

(Let’s not leave the HR bogeyman out of this nightmare. See Big Brother & The Employment Industry: “All your employment are belong to us!”)

However, because the cost of entry to the headhunting business is virtually zero, we’re faced with loads of stupid, inept, and sometimes unsavory “headhunters.” I’d say 95% of those purporting to be headhunters are not. The most common among these are idiots dialing for dollars. (See Why do recruiters suck so bad?) They will solicit thousands of people they know nothing about via mailing lists. As you’ve noted, any good headhunter will know quite a bit about you prior to making first contact, or why would they bother spending their precious time?

2 rules of thumb

I think there are two cautionary notes here — call them rules of thumb to keep you out of trouble. First, assume any e-mail or attachment is a phishing tool. I think that’s a reasonable rule because most e-mail is junk of one sort or other. Very few mails constitute “signal.” Most are noise. So, be skeptical all the time and be very careful.

Second, if it’s a real headhunter, apply basic common sense and business standards. If the mail is from a headhunter you don’t know who clearly doesn’t know you, it’s probably a waste of time. Just because you really, really want a headhunter to find you a job doesn’t make it so. It just ups the odds that you’ll get suckered.

Drop this bomb on the headhunter

To test the sender, simply ask one of the many qualifying questions I list in How to Work With Headhunters… and how to make headhunters work for you. For example, drop this bomb:

“Please give me the names and contact information of 3 people you’ve placed and 3 managers who have hired through you.”

A good headhunter knows how to instantly defuse it by gaining your respect. He’ll ping you back to make sure you’re not going to waste his clients’ time — then he’ll give you his references. The rest aren’t worth dealing with — your question is like a bomb going off on their party. They know it’s all over.

If you’re considering doing something silly just because someone told you to — like clicking on an unknown attachment — ask yourself whether you’d do it in any other business context. If not, then don’t do it. (Would you hire a contractor to remodel your kitchen without checking some references first?)

Beware of fools

Of course, there’s another category of scoundrel — the naïve headhunter who doesn’t consider the risks she asks prospective candidates to take when she sends them solicitations. She’s not worth dealing with, either, because she’s the fool who will accidentally contact your current employer and present your resume for an open position — and possibly get you fired.

How to test for scammers

What you did to test for a scam is what I suggest in HTWWH:

- Google the name of the person who solicited you. Is there evidence the person is affiliated with the firm?

- Google the firm. Is the headhunter that contacted you listed on its roster?

- On the firm’s website, look for names of the owners and for a bricks and mortar address.

- Look up the individuals named, and find the address on Google Maps.

Then ask, does it all add up?

- If there’s no connection between the headhunter and the firm evidenced online, don’t respond.

- If the firm’s website does not list any names, or a street address, or any contact information that you can verify through an independent source, run. (If you do find an address on Google, there should be multiple references to it, or it’s probably phony.)

- While some good headhunters work out of their homes and prefer not to list an address for privacy reasons, they should at least have a verifiable post office box.

- Any real headhunter will have a verifiable phone number and friendly voicemail. Only a scammer doesn’t want to take your call!

Did I say check references?

Did I say check references?

As you found, in most cases there’s no “there” there. If the headhunter fails these tests, checking those references is absolutely critical.

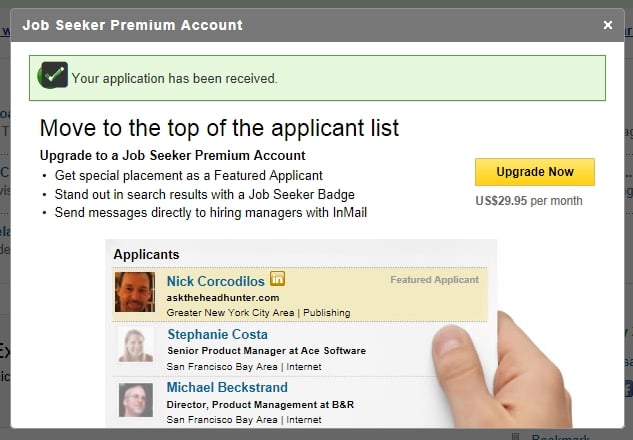

These tests are not sufficient, but they are necessary and they’re a good start when performing due diligence. It’s not hard to determine whether someone is legit, but it’s very easy to be gullible and to get suckered. In this case, a fraud has contacted you — but people should expect that most e-mail solicitations are frauds. The trouble is, most people rationalize: “Hey, I don’t want to miss an opportunity! Besides, this was through LinkedIn.”

Wishful thinking and the pain of job hunting turn people into suckers. (LinkedIn does not confer legitimacy.) “Headhunter” is just another mask scammers wear because they know you’d love a new job. And random job solicitations are just another sign of lousy headhunters that aren’t worth your time or consideration.

(For more on this topic, see How to work with headhunters.)

Did you ever get scammed by a headhunter? Was it even a real headhunter? How do you vet job solicitations?

: :