Question

I recently decided to leave a Fortune 100 company after nearly seven years. I accepted a generous severance package and have just been offered a good job at a small but growing company. I don’t think this company can match my salary demands so I would like your advice on compensation — how to negotiate professionally with them. Thanks.

Nick’s Reply

Job candidates can flub negotiations if they fail to recognize that there are two components to compensation. There’s money, and there’s everything else. If you ignore that dichotomy and focus primarily on the money, you miss the point of compensation and you might forego a job you really want. Of course, if salary is the key for you, then much of this advice won’t be helpful. But if you’re open to alternatives to salary alone, read on.

Job candidates can flub negotiations if they fail to recognize that there are two components to compensation. There’s money, and there’s everything else. If you ignore that dichotomy and focus primarily on the money, you miss the point of compensation and you might forego a job you really want. Of course, if salary is the key for you, then much of this advice won’t be helpful. But if you’re open to alternatives to salary alone, read on.

What is compensation?

Compensation is not necessarily just money. An employer compensates, or “counterbalances or makes amends for” actions you have taken (that is, work you have done) for the employer’s benefit. Viewed this way, compensation might have little or nothing to do with paying you money.

You might think I’m batty, but if you’re forced to negotiate with an employer who can’t meet your salary requirements, suddenly the idea of negotiating beyond money gets interesting. Let’s consider what compensation really means.

What is compensation for?

You devote time, effort, brain power, and perhaps muscle to do a job. These resources are all limited. You deplete them from your life as you deliver them to your employer.

For example, you take time away from your family so you can do the job. Who takes care of your kids? Who grows the potatoes for your dinner? Where do you find time to build a shack to shelter your family from the cold?

If you’re going to tend the job your employer needs done, who will take care of your needs? Simple: your employer. A company must compensate, or counterbalance, for what it takes away from your life — or you will not be available to do the job you’re hired for.

What kinds of compensation are there?

An employer could provide you with housing. (Coal mines used to build entire towns to house their workers. We won’t get into how this system was often abused.) Or, it could give you food. (Restaurants often feed their workers.) In recent times, companies have provided on-site day care for children, or have allowed employees to bring pets to work. If your mortgage, meals, and child care were covered, salary might not be the only salient component of your compensation. You might instead focus on negotiating for a house rather than a shack; for education in addition to child care; and for steak rather than potatoes for your kids.

Did you negotiate for any of those things the last time you entertained a job offer? Maybe you should have, especially when the employer couldn’t cough up the cash you wanted. (See How I negotiate compensation.)

Of course, the list of potential forms of compensation is virtually endless and depends on the company and on you. The challenge is to explore the best, most reasonable alternatives together.

Compensation: Negotiate beyond money

Now, some of these examples are admittedly extreme. But when a company is strapped for cash, should you hang your head and walk away? For better compensation, negotiate beyond money. The smart job hunter knows to shift the negotiation to non-cash, non-salary forms of compensation. You can suggest acceptable alternatives and help the company identify ways to “make amends for” its inability to compensate you in cash. To do this, you must be able to express your needs in terms that can get them satisfied.

Cash futures. If a company can’t match your salary requirements, but you still want the job, don’t fight it. Instead, put other compensation options on the table.

These might include “cash futures”: company stock, an early review with a guaranteed raise, an incentive plan based on agreed-upon performance criteria, guaranteed severance upon termination, elimination of a non-compete clause, or a retention bonus payable once you’ve been on the job for one year.

Salary alternatives. Then there are indirect benefits, on which a company gets a discount (think tax write-off, too), but which deliver value to the employee: computer equipment and other technology to use at home, extended paid vacation, a transportation reimbursement, an expense allowance, child care benefits, a paid cell phone, education benefits, and tax advice services or even payment of taxes (not uncommon for executives).

Priceless time. There’s also quality-of-life compensation: flex time, sabbatical leave, unpaid time off and, nowadays, the freedom to work from home. Most people crave more control over their schedules. You won’t get paid for those summer Fridays off, but if a company can’t afford a full week’s work anyway, you still have a job to go back to on Monday.

Money is great because it’s fungible. It’s an almost universal medium of exchange. It gives us the freedom to buy what we need. But when cash is tight, there’s also freedom in knowing how to negotiate beyond money to get compensated for our work in other ways. You must be able to discuss alternatives, because creative compensation terms might yield a job where there was none.

I’d never suggest taking a job that doesn’t pay well enough, unless maybe if you’re desperate. To be a really effective negotiator, you must be prepared to walk away from any deal that’s not good enough. But before you walk away from a good job with a good employer that “can’t afford you,” try to boost the compensation — negotiate beyond money.

Have you ever foregone higher salary for something else important to you? Have you successfully negotiated beyond money? What are the top three forms of compensation for you? What’s the most unusual form of compensation you’ve received for your work?

: :

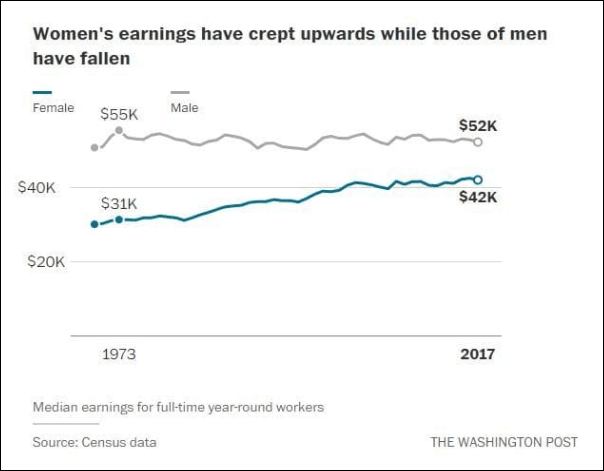

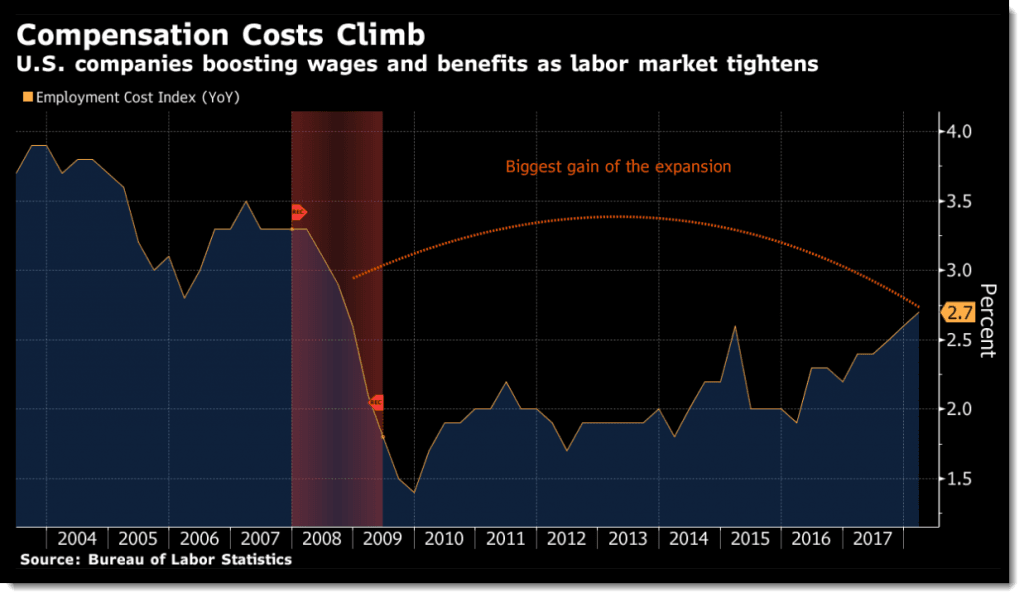

This is the perfect time to negotiate assertively for what you want because employers are dying for good talent. If you’re really good at your work, you have excellent negotiating leverage in the current economy and labor market. I’m glad to hear you got a good salary offer. Now let’s work on that vacation time!

This is the perfect time to negotiate assertively for what you want because employers are dying for good talent. If you’re really good at your work, you have excellent negotiating leverage in the current economy and labor market. I’m glad to hear you got a good salary offer. Now let’s work on that vacation time!

We’re told that whoever mentions a number first in a salary negotiation loses. When employers also demand to know our current salary, that just makes matters worse. So what are we supposed to do in a job interview when this comes up? How do we know how much to ask for and when to do it?

We’re told that whoever mentions a number first in a salary negotiation loses. When employers also demand to know our current salary, that just makes matters worse. So what are we supposed to do in a job interview when this comes up? How do we know how much to ask for and when to do it?

The company I worked for paid me quarterly bonuses for performance but the

The company I worked for paid me quarterly bonuses for performance but the

Employers never make their best offer. You have to negotiate for a few rounds. I’ve read books and articles that give you tactics to improve an offer. I definitely want to get the most money I can, but I don’t want to press so hard that I talk them out of an offer altogether or come off like a jerk. What do you advise?

Employers never make their best offer. You have to negotiate for a few rounds. I’ve read books and articles that give you tactics to improve an offer. I definitely want to get the most money I can, but I don’t want to press so hard that I talk them out of an offer altogether or come off like a jerk. What do you advise?

I want to change jobs because I suspect I’m underpaid. I’ve been looking at Glassdoor and other salary surveys. Are they accurate? How can I find out what salary I should expect from a new job, so that I can figure out if I am currently underpaid, as I contend, or if I should stop my whining?

I want to change jobs because I suspect I’m underpaid. I’ve been looking at Glassdoor and other salary surveys. Are they accurate? How can I find out what salary I should expect from a new job, so that I can figure out if I am currently underpaid, as I contend, or if I should stop my whining?

I was once asked for my tax returns after a job interview, evidently to determine a job offer. I thought you priced a salary to a job — not what you might have to pay a candidate to hire them. I declined the job because the request displayed the kind of people I would be working for. They were forced to sell the company shortly thereafter. What’s your opinion on how to set a salary and job offer?

I was once asked for my tax returns after a job interview, evidently to determine a job offer. I thought you priced a salary to a job — not what you might have to pay a candidate to hire them. I declined the job because the request displayed the kind of people I would be working for. They were forced to sell the company shortly thereafter. What’s your opinion on how to set a salary and job offer?

After months of looking for a job, I finally got an offer using your methods. (Thanks! The interviewer said I was the best candidate she’s talked to in a long time.) But there’s a small matter that concerns me, and it’s not the money. The salary is good. But neither the interviewer nor the HR person would tell me who my boss will be. HR just said I’d be assigned to the manager who needed my skills the most. Then she said they need my answer by end of day tomorrow. Is this a trap? Should I take the job?

After months of looking for a job, I finally got an offer using your methods. (Thanks! The interviewer said I was the best candidate she’s talked to in a long time.) But there’s a small matter that concerns me, and it’s not the money. The salary is good. But neither the interviewer nor the HR person would tell me who my boss will be. HR just said I’d be assigned to the manager who needed my skills the most. Then she said they need my answer by end of day tomorrow. Is this a trap? Should I take the job?

This is the last Ask The Headhunter column for 2018. I’m taking a couple of weeks off for the holidays! See you next on January 8, 2019! Here’s wishing you a

This is the last Ask The Headhunter column for 2018. I’m taking a couple of weeks off for the holidays! See you next on January 8, 2019! Here’s wishing you a