In the May 24, 2016 Ask The Headhunter Newsletter, we dispense with the Q&A and explore some bad news about who’s hogging the profits.

Yes, You’re Getting Screwed

- While the price of fuel has dropped and airlines and their shareholders run to the bank with higher returns, you pay more to sit in smaller airline seats and to arrive at your destination later.

- Your stock broker gets rich off the higher fees you pay on your investments, while the value of your portfolio stagnates or declines.

The trend is hardly worth debating — you pay more to get less. And now we know for sure that it’s hitting your paycheck, too: As corporate profits soar, you get paid less for your work.

I love capitalism, but this isn’t capitalism — it’s greed, and it’s putting our economy and our society at risk because it’s devaluing the work you do and killing your motivation to be more productive.

A banker’s story

A banker’s story

The irony is that a guy at JP Morgan Chase — a big bank making big bucks — has spilled the beans. Bloomberg reports that JPM’s chief economist, Michael Feroli, recently published a research note that reveals — Ta-Da! — “workers’ slice of the economic pie is getting smaller.”

It’s doubly ironic because JP Morgan’s first-quarter profits beat estimates — while the firm slashed bankers’ pay. Even the bankers that are screwing us are getting screwed!

Feroli sharpens the point and explains the connection: As big business gets bigger, there’s a clear link between increasing concentration of ownership and “labor’s declining share… of the value a company creates.”

Which is the long way of saying, you’re getting the shaft while The Man gets richer. The owners of those industries make out while your paycheck gets smaller.

Sheesh — I never thought I’d find myself talking like a workers’ rights nut.

It’s worse than unfair pay

So I’ll make myself clear: While I worry about workers, I worry far more about the gross imbalance between the value of work and what people get paid to do it. Even more than I worry about tired employees’ families going hungry due to stagnant wages and salaries, I worry that American productivity and ingenuity are at risk — because who’s going to be productive and inventive if that behavior is not going to pay off?

It’s worse than you getting paid less. Our entire economic system is at risk because the concentration of ownership and wealth has reached such critical mass that it seems it’s going to destroy itself by ignoring a basic tenet of capitalism — at least according to my definition: Profits spur motivation to do more profitable work when those that create profit enjoy the rewards.

What happens when workers — at any level and in any kind of job — see where the profits are going? I think it spells trouble.

Is Feroli right?

Rather than discussing the regular Ask The Headhunter Q&A column this week, I’d like to ask you to please read Peter Coy’s short article about Feroli’s work in Bloomberg Businessweek: Rising Profits Don’t Lift Workers’ Boats.

And then, if you dare, skim a report written by Jason Furman, chairman of the president’s Council of Economic Advisers: Benefits of Competition and Indicators of Market Power. It’s dense, and one of Furman’s conclusions will seem obvious:

“When firms take action to impede competition, through anticompetitive mergers, exclusionary conduct, collusive agreements with rivals, or rent-seeking regulation to restrict entry, their profitability may increase, but at the cost of even greater reductions in consumer welfare and societal benefits.”

Feroli used this report to map where the value created by various industries goes — and to draw the troubling conclusion that…

“…industries with more concentrated ownership… pay out their extra profits to shareholders, or to the government in taxes, but not to workers.”

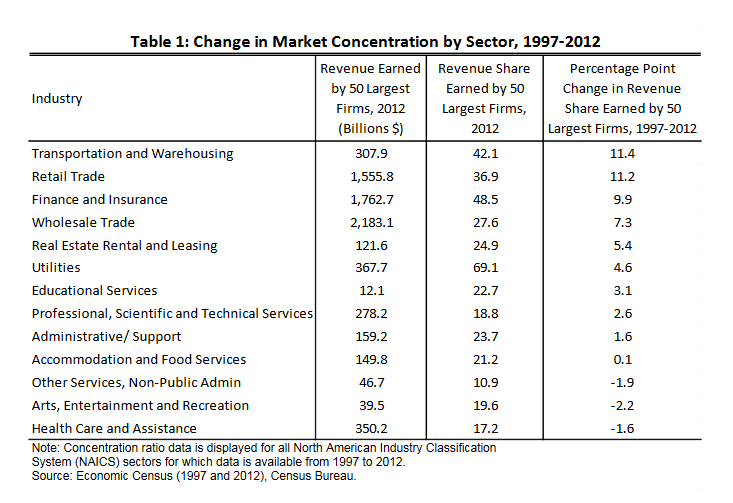

He notes that between 1997 and 2012, in transportation and warehousing, the “share of business accounted for by the top 50 companies rose by 11.4 percentage points,” while in health care and social assistance, it fell 1.5%. What’s telling is that between 1999-2014, in transportation and warehousing, the share of profits paid to employees fell 7.6% — the biggest drop of any industry in the study — while in health care and social assistance, employees’ share of profits rose 1. 8 percentage points.

Draw your own conclusions. Then let’s talk about whether you’re getting paid less — and whether it’s because a concentration of ownership and wealth doesn’t reward the people who come up with the ideas, do the work, and create the wealth.

This week’s takeaway

Since this is Ask The Headhunter and my purpose is to give you a takeaway to help you be more successful — here it is, based on the sources I’ve discussed above: It seems you’ll earn better pay working in an industry where there’s more competition and less concentration of ownership. So pick your job targets wisely.

Feroli’s and Furman’s work suggests, for example, that the healthcare industry pays more of its income to employees, while the transportation and warehousing industries (which includes airlines and railroads) pocket more of the profits and leave workers in the lurch.

Here’s how various industries stack up in terms of the revenue share controlled by their 50 biggest players. According to Bloomberg, Feroli’s analysis suggests “the share workers got tended to decline in industries where there’s more consolidation.” That is, when more revenues are controlled by a smaller number of firms (“consolidation”), the less that industry is likely to pay to its workers.

Of course, being the smart little community you are, you already know which industries are the problem…

If you need help assessing specific employers, these Fearless Job Hunting books will help you with these specific issues:

Book 5: Get The Right Employer’s Full Attention

+ How to pick worthy companies (pp. 10-12)

+ Is this a Mickey Mouse operation? (pp. 13-15)

+ Scuttlebutt: Get the truth about private companies (pp. 22-24)

.

Book 8: Play Hardball With Employers

+ Avoid Disaster: Check out the employer (pp. 11-12)

+ Due Diligence: Don’t take a job without it (pp. 23-25)

+ Judge the manager (pp. 26-28).

How can you tip the balance back towards making your work more profitable to you — when your work is profitable for your employer? Or has our economy shifted so far that it’s going to tip over? In your experience, which industries share the wealth — and which of them pocket the profits you help produce?

: :

“If you are intelligent enough you will find that I’m everything you’re looking for and more. If you are not, then keep on looking…”

“If you are intelligent enough you will find that I’m everything you’re looking for and more. If you are not, then keep on looking…” The big problem is I started to be sexually harassed by a woman co-worker. (I am gay.) This became very uncomfortable. When I finally reached my temp agency, they told me to talk to the woman and tell her (nicely) to take it easy. When I spoke with her, she seemed okay, but then she sent me a very disturbing passive-aggressive e-mail. I forwarded that to my agency and to my on-site manager.

The big problem is I started to be sexually harassed by a woman co-worker. (I am gay.) This became very uncomfortable. When I finally reached my temp agency, they told me to talk to the woman and tell her (nicely) to take it easy. When I spoke with her, she seemed okay, but then she sent me a very disturbing passive-aggressive e-mail. I forwarded that to my agency and to my on-site manager. With the job market being more favorable to employers, they suggest that getting into the dialog too early can remove you from consideration quickly. While none of us wants to waste time going through the motions only to discover the salary may be too low, it may be more important to stay in the game as long as you can, getting them to like you. It gives you more of an opportunity to sell yourself, too.

With the job market being more favorable to employers, they suggest that getting into the dialog too early can remove you from consideration quickly. While none of us wants to waste time going through the motions only to discover the salary may be too low, it may be more important to stay in the game as long as you can, getting them to like you. It gives you more of an opportunity to sell yourself, too. If you think trying to be likeable and saying “I’m sure you’ll be fair” will help you “stay in the game” longer, you’re going to lose because the employer will take advantage of the fact that you invested all that time — and correctly surmise that you’re going to take whatever they offer you. This is one of the oldest psychological tricks used in negotiating — look up cognitive dissonance. People have a tendency to rationalize and accept lousy job offers because they’ve spent so many hours in interviews.

If you think trying to be likeable and saying “I’m sure you’ll be fair” will help you “stay in the game” longer, you’re going to lose because the employer will take advantage of the fact that you invested all that time — and correctly surmise that you’re going to take whatever they offer you. This is one of the oldest psychological tricks used in negotiating — look up cognitive dissonance. People have a tendency to rationalize and accept lousy job offers because they’ve spent so many hours in interviews. I recently got a very nice thank-you note from an applicant to whom I had sent a no-thank-you — that is, a rejection letter. She seemed surprised to hear from me. As a manager, it has always been my practice to reply to every applicant either by letter or e-mail. I’ve been criticized for the time it takes. However, I believe that if someone takes the time to express interest in your company, the least you can do is tell them “no, thank you” if you don’t want them.

I recently got a very nice thank-you note from an applicant to whom I had sent a no-thank-you — that is, a rejection letter. She seemed surprised to hear from me. As a manager, it has always been my practice to reply to every applicant either by letter or e-mail. I’ve been criticized for the time it takes. However, I believe that if someone takes the time to express interest in your company, the least you can do is tell them “no, thank you” if you don’t want them. It’s easy to be rude to a resume; but you can’t hire resumes. Top-notch workers in your field will not stand for rudeness. Talk to all the people you pissed off when you ignored their applications, and you will learn what rude is. Rude is awakening to find your company’s professional reputation has been trashed by good applicants who found out you’re not as good as they are. (See

It’s easy to be rude to a resume; but you can’t hire resumes. Top-notch workers in your field will not stand for rudeness. Talk to all the people you pissed off when you ignored their applications, and you will learn what rude is. Rude is awakening to find your company’s professional reputation has been trashed by good applicants who found out you’re not as good as they are. (See  I want to make a big career change into medical device sales, but it’s going to be tricky. My experience is in teaching, primarily English as a second language. I don’t expect to get a sales job to start, so I want to start out in sales support. I’ve done tons of research on the company I’ve chosen, its technology and products, and I’ve even talked to some of the company’s customers — doctors and medical centers. I know that their salespeople’s time is worth a little over $1,000 an hour, so good sales support is key to profitability.

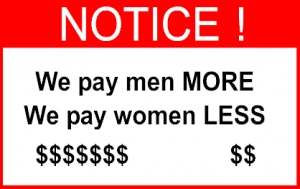

I want to make a big career change into medical device sales, but it’s going to be tricky. My experience is in teaching, primarily English as a second language. I don’t expect to get a sales job to start, so I want to start out in sales support. I’ve done tons of research on the company I’ve chosen, its technology and products, and I’ve even talked to some of the company’s customers — doctors and medical centers. I know that their salespeople’s time is worth a little over $1,000 an hour, so good sales support is key to profitability. The same pundits tell women that they should change their behavior if they want to be paid fairly for doing the same work as men. But the experts, researchers, advocates and apologists are all wrong. There is no prescription for underpaid women to get paid more, because it isn’t women’s behavior that’s the problem.

The same pundits tell women that they should change their behavior if they want to be paid fairly for doing the same work as men. But the experts, researchers, advocates and apologists are all wrong. There is no prescription for underpaid women to get paid more, because it isn’t women’s behavior that’s the problem. Do we need a law?

Do we need a law? Employers who don’t pay fairly will stop getting away with it when they’re required to tattoo their salary statistics on their foreheads — so job applicants can run to their competitors. Or, more likely — since new laws aren’t likely — employers will change their errant behavior when a new generation of women just up and quits. That would be quite a news story.

Employers who don’t pay fairly will stop getting away with it when they’re required to tattoo their salary statistics on their foreheads — so job applicants can run to their competitors. Or, more likely — since new laws aren’t likely — employers will change their errant behavior when a new generation of women just up and quits. That would be quite a news story. I manage a small team, but I’m pretty new to management. Now that it’s time to promote someone, I’m not happy with the criteria my HR department has given me to justify the promotion. It’s frankly nonsense. I don’t want to promote someone just because they’ve been on the job for two years. I want to use the opportunity to really assess whether they are ready for more responsibility and some new authority, and to help the employee realize what this means for them, for my department and for our company. Do you have any suggestions for how I should handle this so it will mean something?

I manage a small team, but I’m pretty new to management. Now that it’s time to promote someone, I’m not happy with the criteria my HR department has given me to justify the promotion. It’s frankly nonsense. I don’t want to promote someone just because they’ve been on the job for two years. I want to use the opportunity to really assess whether they are ready for more responsibility and some new authority, and to help the employee realize what this means for them, for my department and for our company. Do you have any suggestions for how I should handle this so it will mean something?

Instead of just turning down my counter-offer and staying at $80,000, which I would’ve gladly taken, they rescinded the offer completely. The hiring manager wouldn’t even respond to my calls or e-mails, even after he said he’d be glad to discuss any questions.

Instead of just turning down my counter-offer and staying at $80,000, which I would’ve gladly taken, they rescinded the offer completely. The hiring manager wouldn’t even respond to my calls or e-mails, even after he said he’d be glad to discuss any questions.