In the May 29, 2018 Ask The Headhunter Newsletter we take a look at how companies recruit the same and why it’s unwise.

Question

I run a sizable company. Like our competitors, we’re finding it difficult to recruit the people we need to grow our business. We all talk about competitive advantage being the crucial factor, and I’ve always believed a company’s competitive advantage comes from its people. But it’s easier said than done to find people with the skills we need. My vice president of HR gave me some of your articles and I find what you say troubling, that the tools we’re using to find talent are leading us astray. It’s easy enough for a headhunter to say that. Can you back up your claims that we’re doing it wrong?

Nick’s Reply

When I do presentations for Executive MBA (EMBA) programs at schools like UCLA, Wharton, Cornell, and Northwestern, I always take the opportunity to ask one of my favorite questions: How do you actually recruit the people you need to hire?

The managers in the audience — who are investing a lot of money to learn how to leverage talent into profits — almost always answer like this: “We create detailed job descriptions and post them, or we use headhunters.”

Then I make them nervous and ask why they pay a headhunter $30,000 to fill a $120,000 position, if they can just post jobs for five bucks apiece.

“Well, sometimes we need help.”

And how many candidates does the headhunter deliver?

“Usually four or five.”

Algorithms don’t recruit

Now I’ve got them. But I’m not trying to sell them headhunting services. I want them to realize that one recruiting method delivers just a handful of good candidates, while the other — automated, algorithmic recruiting — turns on a fire hose of applicants that all their competitors are looking at, too.

Why don’t they go off the beaten track and use a competitive recruiting advantage? I suggest that they should invest the time—personally—to go out into their professional communities and recruit as few candidates as possible, but make sure they’re all the right ones. (See Talent Crisis: Managers who don’t recruit.)

Their answer is embarrassing, and it usually goes like this:

“That’s incredibly time intensive! We have this model: We post a job description, and we get 2,000 applicants. But you want us to risk everything—all this time and effort—on four or five applicants? What about the other 1,995 applicants? What do we do with them?”

“You take a pass,” says Gilman Louie, a venture investor who rejects mass recruiting methods. And I think he’s absolutely right. Don’t listen to me. Listen to him.

What a VC knows about hiring

Gilman Louie is a founder of Silicon Valley VC (venture capital) firm Alsop Louie Partners, which invests in sectors including security and privacy, data and analytics, consumer products and services, and education technologies. In the 1980s Louie licensed the blockbuster video game Tetris from its developers in the Soviet Union. He’s also listed as one of 50 scientific visionaries by Scientific American.

You and your HR department would do well to consider that Louie is probably much more successful at hiring than your company is because he knows how to recruit. He doesn’t rely on LinkedIn, job postings, and the mass recruiting efforts HR departments use.

Employers love to proclaim their goal is to find the unusual, the star, the talent that will lead the organization into the future. So why does virtually every company rely on a recruiting method that’s designed to deliver staggering numbers of “candidates” that are all wrong?

You’re using the same algorithm

Gilman Louie: “Because of the competition for talent, employers are unfortunately using those typical HR filtering systems to put resumes in the right piles and to line up the interviews. The problem with that is, whether you’re an established company or a start-up, everybody has the same algorithm.”

I tested the question I ask EMBA students on Louie: “You can get 2,000 resumes online for about five bucks. Why not just get lots of candidates into HR’s pipeline?”

Louie: “You can’t go through 2,000 candidates! HR processes 2,000 candidates! They don’t look through 2,000 candidates! And at the end of the process, what they get is the same candidate that everybody else running PeopleSoft gets! So where’s your competitive advantage if everybody turns up with the same candidates?”

Eliminate the perfect resumes

You don’t review lots of resumes to find the best candidates?

Louie: “I put a job description out and all this stuff starts flowing in. I lay out those 100 or 1,000 resumes, or those LinkedIn files—and, all the things that everybody has that are the same, I just draw a line through them. What’s left over is what I look at because I’m trying to find the thing that distinguishes one candidate from another candidate. I’m not looking for the perfect resume. The perfect resume is vanilla.”

Louie spends a lot of time in his professional community meeting people. (See The Manager’s #1 Job.) That personal investment in face time yields the best hires for the startups he funds.

Go where your competitors are not looking

For example, Louie teaches MBA classes at Vanderbilt and Stanford Universities. He explains why it’s so important to go out into the wild and recruit in person.

Louie: “I recruited a kid who was a high-school dropout during a presentation we did at MIT. He was clearly different from all the other students. So I went and asked the admissions department about him. They said, when we interviewed him, one of our admission officers recognized the custom bikes the kid made when he lived on the wrong side of the tracks in Glasgow. He said, ‘We need this kid; he’s entrepreneurial! He doesn’t look like any of the other kids. He has a mediocre GPA, doesn’t have straight As, didn’t go to a private school, didn’t have any of the things MIT kids have. The resume popped.’ So he got in because he was different. We hired him, and he’s phenomenal.”

Employers look for their hires on LinkedIn, via job postings, and through the mass recruiting efforts of their HR departments. Louie refers to the kind of thinking that’s behind such hiring methods as too conventional, or “on the line.”

Get off the line

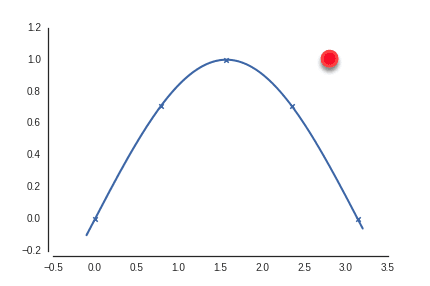

Louie: “The question that Steve Jobs always asked was not about the way the world is going to be, but the way the world should be, based on his point of view, based on his distorted reality. It’s some place off that line. So the trick is to get off the expected path line. It turns out, by the way, if you do the actual analysis, the world never turns out to be on that line. And the reason for that is, all the incentives go to the guy who figures out how to move off that line!”

If that sounds like natural selection—survival of the winner—it is.

Louie: “All the value that you create between the line you are on and the line everybody else is on is yours. When you’re selecting people, you can’t select people who are going to be on that line. You’ve got to select people who are off that line.”

Competency is not competitive advantage

Let’s get back to your question about whether the algorithmic recruiting tools your company uses are leading you astray. Your company’s HR department is not recruiting in some pool of rarefied talent, like Gilman Louie does when he sits in on a seminar comprising unusual participants. (See Smart Hiring: How a savvy manager finds great hires.)

Your HR department is drowning in the same rush of job applicants fed through the same fire hose every other HR department subscribes to — Indeed, LinkedIn, ZipRecruiter, Taleo, and a raft of other undifferentiated keyword-matching systems. Worst of all, you’re paying dearly for their services.

Louie: “Here’s the problem with the algorithms. The algorithms are all looking for the same. Everybody is fighting for a handful of talent that the algorithm brings up. This jacks up the price, and it communicates that employees are kind of fungible. Employees are not fungible. I’m not saying those tools aren’t helpful. They will get you to competency. But competency is not competitive advantage. Competitive advantage is finding the unusual that everybody else missed.”

It’s personal

Gilman Louie makes it very simple when I ask him to summarize how he hires for competitive advantage.

You just told us three crucial things. One, you recruit by watching people in their native habitat. Two, you find people others missed. Three, you don’t rely on resumes, you go ask someone.

Louie: “Exactly.”

None of those steps have anything to do with traditional or automated recruiting.

Louie: “You’ve got to get there, and it’s personal. And personal is not digital.”

(Gilman Louie’s comments are from a discussion I had with him a few years ago while working on another project. If I thought he was prescient about “digital recruiting” back then, now I think Gilman’s advice is timeless wisdom.)

What does this venture investor’s advice about hiring tell us about the state of recruiting in today’s economy? Can these methods work in normal company settings? If you’re an employer — a hiring manager or an HR exec — can you “get off the line?” How can you put these ideas to work if you’re a job hunter?

: :