In the April 26, 2016 Ask The Headhunter Newsletter, a hiring manager lectures employers about the importance of no-thank-you notes — and about respecting job candidates.

Question

I like your suggestions about thank-you notes. However, I want to talk about no-thank-you notes.

I recently got a very nice thank-you note from an applicant to whom I had sent a no-thank-you — that is, a rejection letter. She seemed surprised to hear from me. As a manager, it has always been my practice to reply to every applicant either by letter or e-mail. I’ve been criticized for the time it takes. However, I believe that if someone takes the time to express interest in your company, the least you can do is tell them “no, thank you” if you don’t want them.

The convenience of job boards and e-mail applications has led us to forget there are real humans with feelings at the other end. Since we are not likely to run into one of them at the check-out counter, we don’t acknowledge that every resume sent out to us carries this person’s real hopes for a job along with it.

I would encourage you to write a bit about etiquette for the hiring manager and about the proper approach regarding the communication to applicants after receiving their resumes.

Nick’s Reply

Hallelujah! I hope everyone who reads your statement tacks it to a couple of doors: the boss’s and the human resources (HR) department’s. But don’t forget the board of directors. It ought to be tacked to their agenda.

Who has time to be nice?

You’ve given me a chance to hold forth on a subject that’s always too easily dismissed. The story today is that companies receive so many resumes and applications that there is simply no way to respond to them all. HR departments scoff at the suggestion that they’re responsible for such niceties. Who can reply to 5,000 job applicants and still have time to hire anybody? The trouble is, HR sets this standard for all managers in a company.

Somewhere along the way, maybe after getting intoxicated by the millionth resume she downloaded from LinkedIn, an HR manager lost sight of the thousands of job applicants she had lined up outside her door (actually and virtually). She forgot that if you invite them, you have to feed them. She forgot that when you post jobs on websites that encourage thousands of people to send you resumes, you get thousands of resumes. However, you don’t hire thousands of people. So, why solicit them? (See Employment In America: WTF is going on?)

When we create situations that make it impossible for us to respect basic social conventions (like saying “thank you” and “no, thank you”), that should be a signal that we’re doing something fundamentally wrong.

Stop behaving like wild dogs

Why solicit thousands of applicants, when you need just a handful of good ones? When you get sick from overloading your plate at the cheap buffet table, nature is telling you something. When we let the dogs go wild at feeding time — HR rabidly devouring heaps of non-nutritive resumes — it’s time to re-train the dogs. But I’m not lashing out only at HR managers. Nope. I’m lashing out at their trainers: departmental managers, corporate CEO’s, and boards of directors.

Are you on a board? Are you a CEO? Do you have any idea how your HR department and your managers are treating the professional community you so desperately need to recruit from? Make no mistake. Even in today’s “employer’s market,” top-notch workers continue to be few and far between. Finding those few precious souls who can both do the work and bring profit to your bottom line is a daunting, challenging task. To get the attention of the best, the brightest… you’ve got to be nice to everyone.

Your company is under the spotlight every time you recruit to fill a position. The behavior of your HR department, your managers, and your employees reflects your company’s values. And your values affect your success at hiring. Yah, that’s right. Don’t proclaim to your shareholders that “people are our most important asset” while your underlings shove job applicants through keyword algorithms like meat through a grinder. (See Reductionist Recruiting: A short history of why you can’t get hired.)

Be Nice: Say thank you

This is a wake-up call about behavior. Every company’s reputation hinges on it. Ask your mother; she’ll tell you. Always say thank you. Always wear clean underwear. Always take time to be polite to people.

- If you have no time to write thank-you notes, then you’re soliciting too many resumes.

- If you have no time to get out of your office and meet the movers and shakers in your professional community, you’re not recruiting; you’re pushing paper. (See Ten Stupid Hiring Mistakes.)

- If you have no time to be nice, I’ll bet it’s because you spend too much time with resumes and not enough with people.

It’s easy to be rude to a resume; but you can’t hire resumes. Top-notch workers in your field will not stand for rudeness. Talk to all the people you pissed off when you ignored their applications, and you will learn what rude is. Rude is awakening to find your company’s professional reputation has been trashed by good applicants who found out you’re not as good as they are. (See Death by Lethal Reputation.)

It’s easy to be rude to a resume; but you can’t hire resumes. Top-notch workers in your field will not stand for rudeness. Talk to all the people you pissed off when you ignored their applications, and you will learn what rude is. Rude is awakening to find your company’s professional reputation has been trashed by good applicants who found out you’re not as good as they are. (See Death by Lethal Reputation.)

Learn to be nice. Make it your policy.

If you don’t inspire good people to say nice things about your company, you can’t hire good people. It starts with that thank-you note; even with a no-thank-you note. Where it really starts is with your hand writing a personal note; with that hand attached to an arm attached to a warm body that gives a damn. Because if you don’t give a damn about people who apply to your jobs, pretty soon everybody will know, including your shareholders.

And that, Mr. CEO and Ms. Member of the Board of Directors, is why you need to make sure your HR department and your managers are polite, wear clean underwear, and write thank-you notes.

Does your company respect job applicants? Does it walk the talk — and send thank-you notes? Does your HR department insist on proper behavior from job applicants, and then diss them when the interviews are done?

: :

I want to make a big career change into medical device sales, but it’s going to be tricky. My experience is in teaching, primarily English as a second language. I don’t expect to get a sales job to start, so I want to start out in sales support. I’ve done tons of research on the company I’ve chosen, its technology and products, and I’ve even talked to some of the company’s customers — doctors and medical centers. I know that their salespeople’s time is worth a little over $1,000 an hour, so good sales support is key to profitability.

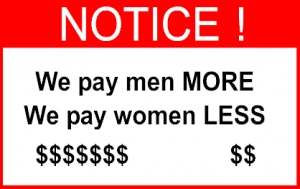

I want to make a big career change into medical device sales, but it’s going to be tricky. My experience is in teaching, primarily English as a second language. I don’t expect to get a sales job to start, so I want to start out in sales support. I’ve done tons of research on the company I’ve chosen, its technology and products, and I’ve even talked to some of the company’s customers — doctors and medical centers. I know that their salespeople’s time is worth a little over $1,000 an hour, so good sales support is key to profitability. The same pundits tell women that they should change their behavior if they want to be paid fairly for doing the same work as men. But the experts, researchers, advocates and apologists are all wrong. There is no prescription for underpaid women to get paid more, because it isn’t women’s behavior that’s the problem.

The same pundits tell women that they should change their behavior if they want to be paid fairly for doing the same work as men. But the experts, researchers, advocates and apologists are all wrong. There is no prescription for underpaid women to get paid more, because it isn’t women’s behavior that’s the problem. Do we need a law?

Do we need a law? Employers who don’t pay fairly will stop getting away with it when they’re required to tattoo their salary statistics on their foreheads — so job applicants can run to their competitors. Or, more likely — since new laws aren’t likely — employers will change their errant behavior when a new generation of women just up and quits. That would be quite a news story.

Employers who don’t pay fairly will stop getting away with it when they’re required to tattoo their salary statistics on their foreheads — so job applicants can run to their competitors. Or, more likely — since new laws aren’t likely — employers will change their errant behavior when a new generation of women just up and quits. That would be quite a news story. I manage a small team, but I’m pretty new to management. Now that it’s time to promote someone, I’m not happy with the criteria my HR department has given me to justify the promotion. It’s frankly nonsense. I don’t want to promote someone just because they’ve been on the job for two years. I want to use the opportunity to really assess whether they are ready for more responsibility and some new authority, and to help the employee realize what this means for them, for my department and for our company. Do you have any suggestions for how I should handle this so it will mean something?

I manage a small team, but I’m pretty new to management. Now that it’s time to promote someone, I’m not happy with the criteria my HR department has given me to justify the promotion. It’s frankly nonsense. I don’t want to promote someone just because they’ve been on the job for two years. I want to use the opportunity to really assess whether they are ready for more responsibility and some new authority, and to help the employee realize what this means for them, for my department and for our company. Do you have any suggestions for how I should handle this so it will mean something?