In the September 10, 2013 Ask The Headhunter Newsletter we tackle 5 nightmares:

- An employer wants free work

- A relocation dream turns into a horror story

- A guy’s network POOF! disappears into thin air

- LinkedIn makes an employer tell job seekers to sleep it off, and

- A headhunter and his client are lost in salary dreamland…

I get a lot of questions from readers, and I sometimes reply via e-mail with short answers (when I have time) that I never publish. But some of them are just as worthy of discussion… so here we go with some short(er) ones!

Question 1: They want free work!

Your column regarding working on a real problem during the interview hit home. In the past six months I’ve had two interviews where I have been asked to work on a real-world problem. The first time, I suspected that this “interview” was to get an outsider’s opinion on a problem the staff was working on. (They wanted free work.) I never heard from the employer again. The second time, I asked the interviewer if the problem was something they were working on. He said yes and that this was a way for them to get a combination of interview and consulting work! I finished the problem and sent them an invoice for the time I spent at the firm. I can appreciate demonstrating your skill to a potential employer. However, the candidate has to be on guard for those seeking free work. How to handle these situations?

Your column regarding working on a real problem during the interview hit home. In the past six months I’ve had two interviews where I have been asked to work on a real-world problem. The first time, I suspected that this “interview” was to get an outsider’s opinion on a problem the staff was working on. (They wanted free work.) I never heard from the employer again. The second time, I asked the interviewer if the problem was something they were working on. He said yes and that this was a way for them to get a combination of interview and consulting work! I finished the problem and sent them an invoice for the time I spent at the firm. I can appreciate demonstrating your skill to a potential employer. However, the candidate has to be on guard for those seeking free work. How to handle these situations?

Nick’s Reply

When I emphasize the importance of “doing the job in the interview,” I usually include a warning about not working for free. That’s an abhorrent way for an employer to get free work from a job applicant — but I’ve seen it done many times. When responding, it’s always best to be a big cagey, and to hold back some details. If they press you, smile knowingly and offer your consulting time (for a fee) while they complete their hiring process. Heavily detailed “sample problems” are a tip-off. Do just enough to whet their appetites.

Question 2: Relo nightmare

My company relocated me to a new city in another state to a job with the same description as I had before. I thought it was going to be great. Unfortunately, I hate it. There are spider webs and low lighting everywhere, and I dread going to work every day. They got me to sign a contract — I have to repay relo costs of $12,000 if I leave before two years. It’s all of my savings. I am feeling stuck at this not-as-advertised job. I’ve certainly learned a lesson about getting a tour of the site before signing a contract. Am I totally stuck?

Nick’s Reply

Ouch. Relo can be a kind of indentured servitude. Since a contract is involved, I think your best bet is to see an attorney. You can probably get an initial consultation at no cost, but I’d get a good referral from a trusted source. The alternative is to feel depressed for two years. I’m not a lawyer and this is not legal advice, but you might be able to show that the job is not what they “contracted” for. I wish you the best.

Question 3: My network disappeared

I am a senior software consultant. I recently hit a dry spell finding work and finances have become very tight. What’s alarming is the realization that I am not really connected to any sort of reliable, non-virtual network that can help get me back in the game sooner. I guess while I am actively working, I don’t really think about it. Instead, my de-facto “network” is a random collection of job boards, fruitless job agents, and a few incredibly rude recruiters. Clearly this is inadequate. How do I tap into the support system I desperately need during the down times?

Nick’s Reply

You can’t tap into a support system you don’t have. A big part of life and work is cultivating friends and relationships over time. Please see Tell me who your friends are.

Frankly, a support system is more important than any job. I’m not talking about a loose network of “contacts” for that purpose — I’m talking about real friends and buddies. Attend conferences. Join groups. Take training classes. Offer to do presentations. Cultivate and invest in your relationships — not just professionally, but in all parts of your life. You’ll know you’re doing it wrong if it’s not enjoyable.

Question 4: LinkedIn & ruled out

Thanks for your eye-opening article on LinkedIn. If I were an employer looking to hire (which I was when I was starting my small but successful software company about 20 years ago), I would respond to the sleazy practice of paid uplisting by working my way down the list and e-mailing anyone who had paid for an uplist. I’d let them know that I would not consider them for the job because they had clearly indicated that they didn’t consider themselves good enough to stand on their own merits.

Nick’s Reply

What puzzles me is why job seekers don’t get past the guard (the online forms and the HR department), and why hiring managers don’t open the door to the most motivated applicants! (If you liked that LinkedIn article, see the extended one I wrote for PBS NewsHour.)

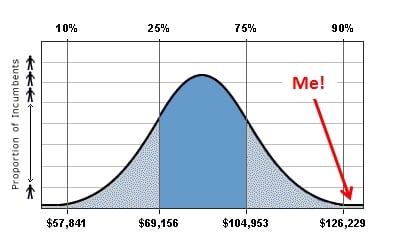

Question 5: Salary nightmare

I recently had a discussion with a headhunter for a well-known staffing agency who insisted on getting my current salary. He told me the pay range for the position was $80k-$100k and that if $80k was more than 10% above what I’m currently making, he couldn’t offer me the position. I told him that $80k was more than 10% above what I’m making now, but I refused to give further details. He asked a few more times for my salary and finally ended our “interview” by saying he’d submit my resume and see what happens. What happened here? Is this B.S.? Who said I can’t make more than 10% higher in a new position?

Nick’s Reply

No one says you can’t make more than 10% higher, except this “headhunter’s” client. Many headhunters merely parrot what their client tells them. That’s a poor way to service a client. Sometimes you’ve got to tell them what they need to hear — not what they want to hear. His laziness further reveals itself in the fact that he won’t even back up his client — he’s still going to submit your resume! It’s not clear what he’s really doing to earn a fee. He’s waiting to see if some spaghetti might stick to the wall. Who knows, maybe he’s got no other candidates to submit and he’s willing to chance it.

Of course, employers have the right to limit job offers, even if the limit is completely irrational. The next candidate might be making $90k, so the top offer would be $99k. If you’re making $70k, but can do the job, and they gave you $80k — more than a 10% bump — they’d be saving money, right? Go figure. There are idiots in HR departments who can barely count their fingers and toes, and they’re making these kinds of salary calculations? The decision you must make is, do you want to work with an employer or a headhunter like these two?

I’ve placed people for close to twice their old pay. And the client and the new hire were perfectly happy — value delivered and paid for with no regrets. If I were you, I’d move on to a headhunter and an employer whose goal is to hire good people, not to learn how to count their fingers and toes. (See How to Work With Headhunters… and how to make headhunters work for you.)

My compliments for holding fast and not disclosing your salary history — but you let the cat out of the bag anyway. Next time, just say the job seems to be in the right salary range in terms of what you want. Of course, later on, if they make an offer, you must hold fast and not disclose what you’re making. (See Should I disclose my salary history?)

I’m sure you’ve got your own advice to offer on these little nightmares. Please pile on!

: :